The playground in an amazing way gathers the hopes and despair of today’s society, perhaps much more than any other public art project because it needs fewer resources to build and is immedially accessible to the public.

This project is about playgrounds; understood as places that embody both the hopes and despairs of contemporary society.

Nika Dubrovsky, curator:

This new project is about playgrounds; understood as places that embody both the hopes and despairs of contemporary society.

The origins of the project can be traced back to discussions in the Pedagogies of Care room led by Andris Brinkmanis—in particular, his meeting with the Contrafilé group. Based in Sao Paulo, Brazil, Grupo Contrafilé is an art-politics-education production group that focuses on encounters with different people and communities—always from a cartographic perspective—whose primary medium is the performatization and observation of urgency.

PLAY(GROUNDS) // GROUNDS OF PLAY is currently being developed in a hybrid format. Firstly, online, as a room at the Museum of Care: a resource which everyone can use and contribute to. The room features a collection of materials about playgrounds, both real and fictional.

Secondly, offline, as part of the upcoming “Discussion Circles” programme at Saint Vincent where a presentation will be delivered on June 22nd. Speaking at this event will be Nika Dubrovsky, Clive Russell, John Phillips, and Andris Brinkmanis.

The playground is a political space that mirrors social changes, showcasing our views on public welfare, education, and play.

Playgrounds vary widely: some depict space travel, while others advertise products to kids and their parents. Some designs encourage performance art, while others promote segregation between classes or even races. As government funding for public projects fluctuates, and as society becomes either more bureaucratized and securitized or freer and safer, so too do the aesthetics and designs of our playgrounds evolve.

The French and Russian revolutions began by taking over major palaces and converting them into Museums (the Hermitage and the Louvre) to symbolize a transfer of power from kings to citizens. Just imagine what could have happened if revolutionaries would have decided to take over millions of playgrounds instead of royal palaces? What kind of revolution would start from the creation of free and safe public learning and playing spaces all around the country?

In a way, this is what the Russian Proletkult attempted in the first 2-3 years after the Russian Revolution, before they were crushed by Stalin’s regime. But, even so, we still feel its influence on our lives even today.

Why am I interested in this theme?

In the endless amount of time I’ve spent on playgrounds while my kids were playing, I became a fan, as well as a hater, of the many that exist in the various countries that I visited, and came up with all sorts of ideas for my own playgrounds, too. In ’90s Russia, my little daughter played on a playground covered in ads for cheap yogurts; in New York in the 2000s, my son played on a playground made mostly out of security specs, that were put in place to prevent playing instead of facilitating it; later, in Berlin, he steered a pirate ship on a beautiful playground built in a Turkish neighborhood by enthusiasts who seemed to have escaped all limitations and construction codes. It was an immigrant Nuekoln community, probably authority did not pay much attention to it, but at that time (2000s) Germany was much more loose on regulation, compared to the US.

This type of playgrounds might look criminally dangerous to any US parents, but in fact, it’s creative, inventive, and their safety is organized by a community that builds it for themselves and by themselves. Interestingly, there were no mass shootings in Germany at that time, but it was actually the US that had this problem while simultaneously increasing all kinds of police-run “safety” measures.

After spending lots of time at playgrounds with their children, many parents start to think about their own ideal playground. Why don’t all of us—current and future parents—create our own APTART home exhibits focused on one of today’s most vital public arts: crafting spaces where people of all ages and backgrounds can play together?

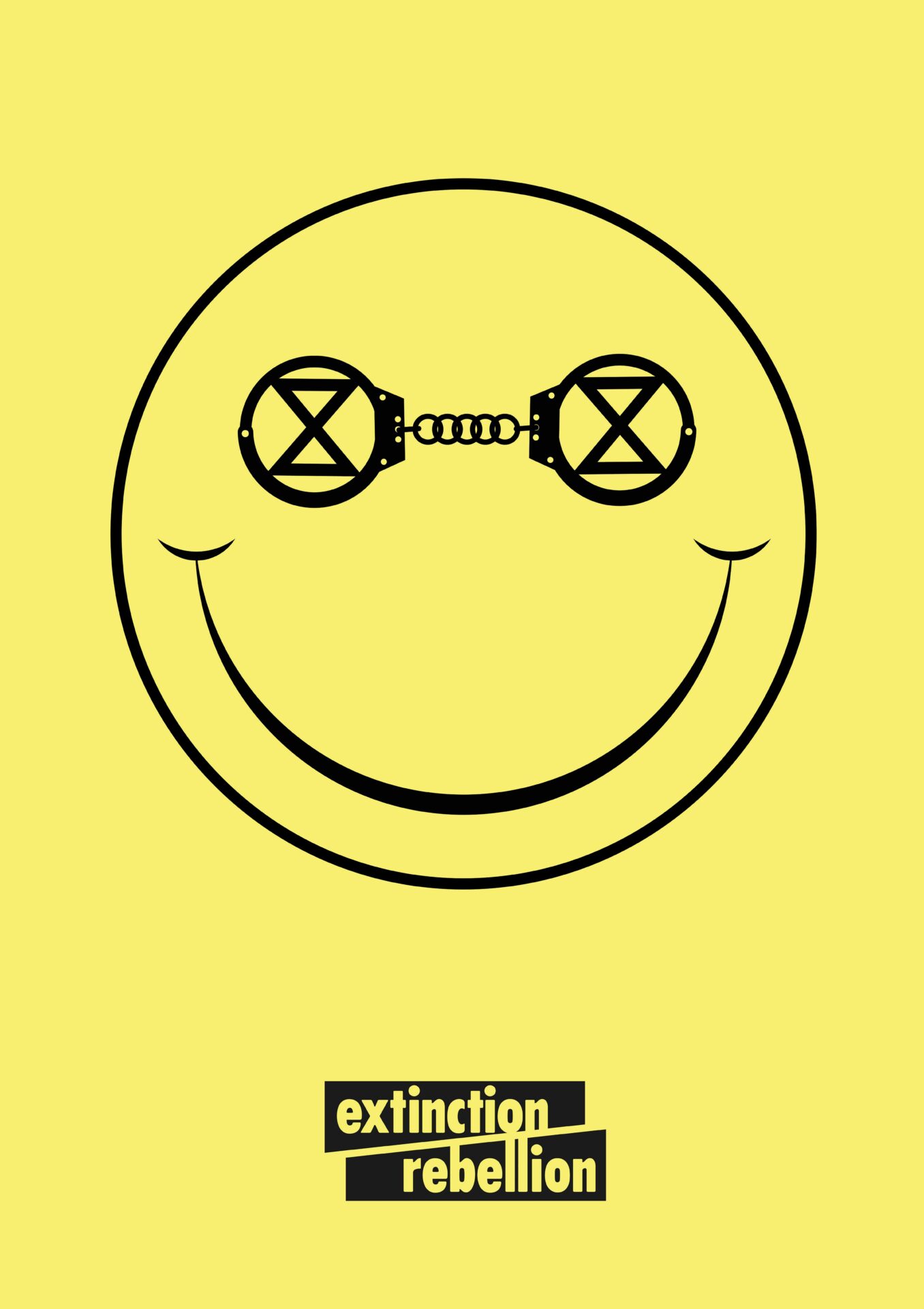

David Graeber and I once started a project called Visual Assembly. It was devoted to what we called the City of Care. Our friends from the Extinction Rebellion Art Group helped us put it together.

It turned out that a space for play—where people of all ages come together—is a very important part of city life. I was thinking it might be interesting to come together and discuss in more details what playgrounds could look like.

And what is a playground anyway?

A playground can be a place where children are protected from the dangerous adultworld and the adult world gets rid itself of cumbersome children, but it can also be a place for trying out different ways of connecting to each other and fostering social imagination;. A place where people meet, communicate, plan their future, and ultimately where the reproduction of culture takes place.

Working in Madagascar, David Graeber observed that the community assemblies organized by locals were fun festivals, with songs and entertainment , which made them both accessible and desirable for everyone. Compare it with our western meetings, where we use excel files, voting and have to listen to long speeches of the organizers and front runners.

So, this room will host discussions around possible ways of building playgrounds, book presentations and documentation of our own exhibitions and events connecting to the theme of playing, learning and being together.

Andris Brinkmanis, curator:

Playgrounds are spaces that apparently, share similar design patterns all over the world. Yet what is fascinating, that when taking a closer look they differ and offer various modes of usership. As any pre- designed spaces, they are devices of homologation, but also places where unexpected creativity may unfold. Play, as Giorgio Agamben has underlined is a fundamental element within the process of profanation. and profanation is one of those actions that can still allow us to regain the right of usership of those tools that have been codified and rendered inaccessible to us. Perhaps, we may use playgrounds both as a physical space and a metaphor that can help us to come up with new ideas for the social sphere.