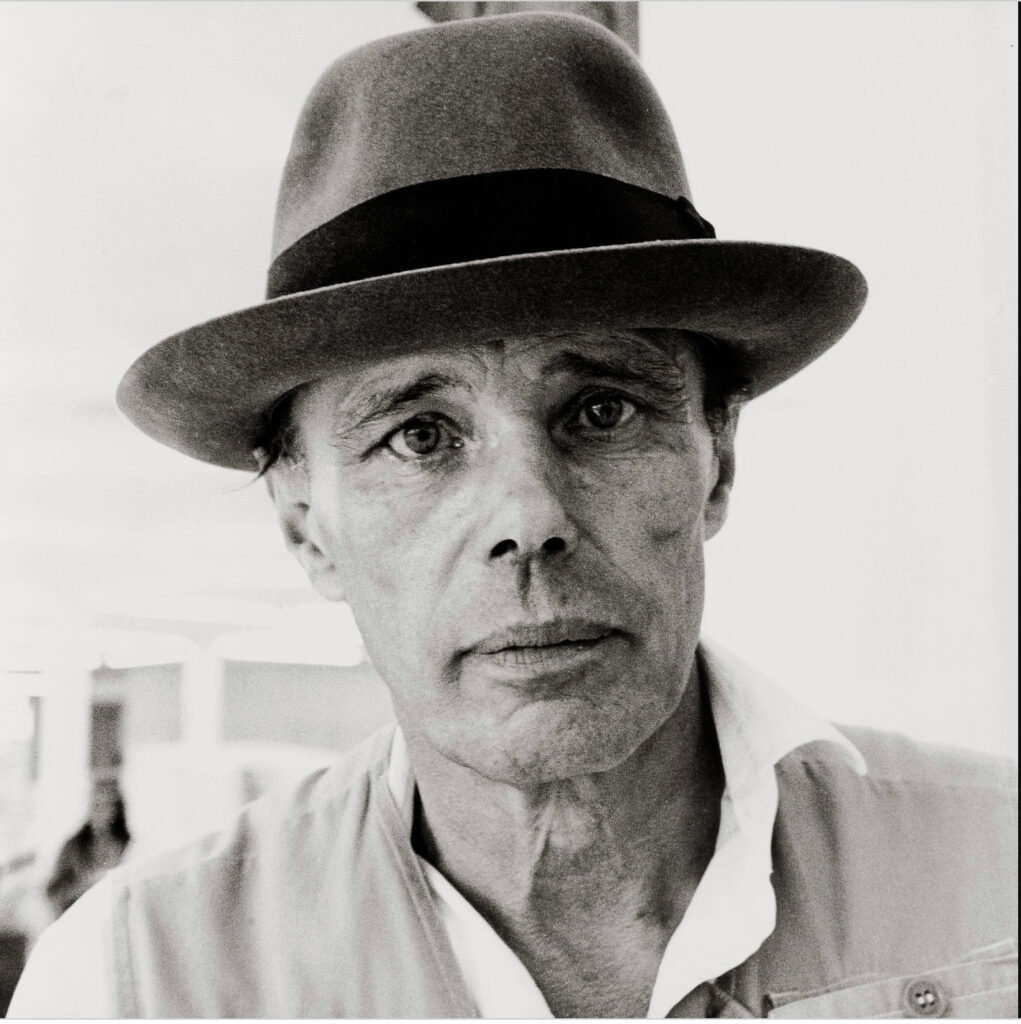

Two of the most famous German artists were not friends.

They were both engaged in participatory art and both strongly influenced our view of society. Yet their visions were radically different: Beuys called Walter a bureaucrat and a tailor. And Franz Erhard Walther felt humiliated and lonely in Boyce’s circle, so he lived in isolation for years until conveniently for him the neoliberal times arrived. Already an elderly artist he became an international celebrity.

Franz Erhard Walther VS Joseph Beuys didn’t have a chance to have a heart-to-heart talk with each other, and as equals, because Beuys was Walther’s teacher, but I think this dialogue would have been very important for us to hear. I want to know what they have to say to each other about freedom, about the relationship between people and objects (and people and material culture in general).

Beuys’ work came at a time when it seemed possible to change everything – to build new political parties that would end the war and save nature from being destroyed by capitalism.

Franz Walther’s work came at a time of the triumph of neoliberalism, of fading hope, despair and apathy His work, as Caroline Lillian Schopp correctly points out, can only be considered political in the sense that they allow viewers to experience how to be unfree rather than how to liberate or solidarize with one another:

The equivocality, purposelessness, and openness of Walther’s work actually requires users to assume odd positions of physical vulnerability and to undertake disturbing activities steeped in uncertainty about what one is doing, for how long, and why. It generates certain kinds of affect, such as angst, embarrassment, self-consciousness, and insecurity. It often does this by hindering the able body. Blindobjekt (Blind Object), no. 12, 1966, is a heavy sack of thin foam rubber lined inside and outside with brown canvas. It has the look of a sleeping bag. The user would put it over their head and then attempt to find their way around. The activation thus involving being stifled and blinded, at once concealed and vulnerable, camouflaged and exposed. It is in this way that Walther’s early work might be understood to be political-not because it is liberatory, but because it is not.

The Venice selection committee lauded Walther for work that “continues to activate the viewer in engaging ways. The question, of course, is who activates whom: the viewers the objects or the objects the viewers.

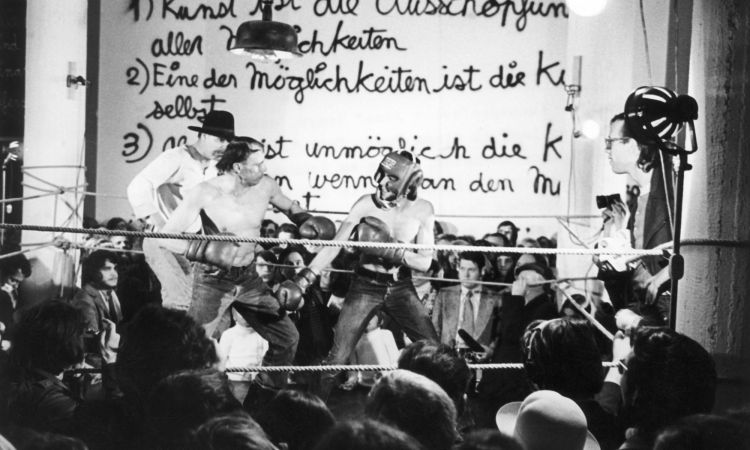

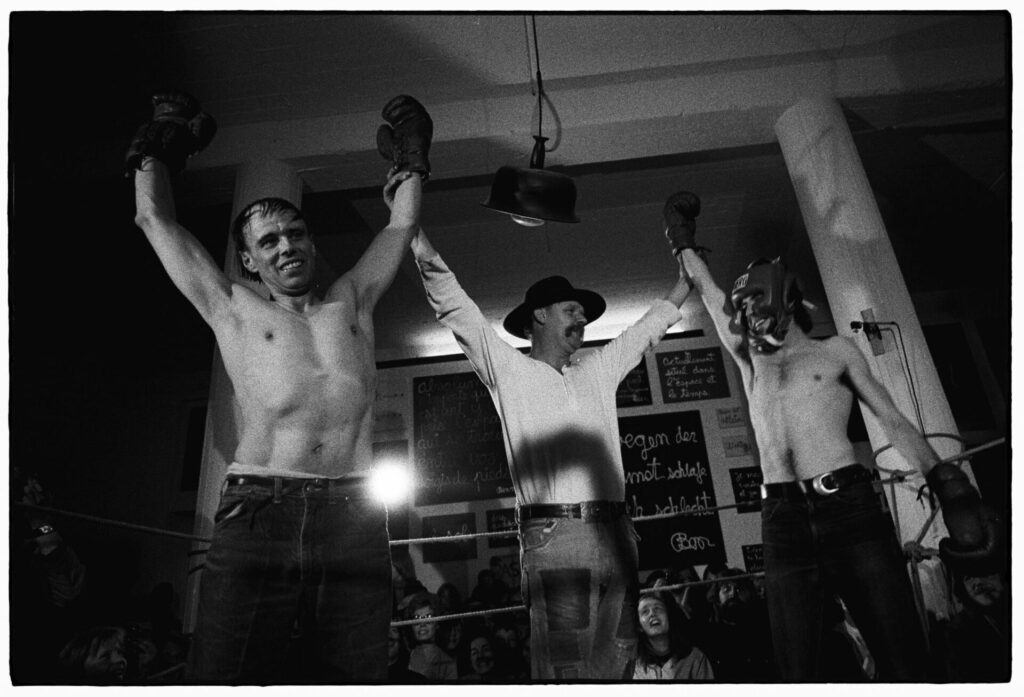

Boyce fought for direct democracy in the literal sense of the word, not only by setting up a ring on Documenta, but also by becoming one of the organizers of the German Green Party.

Walther spreads out his beautiful textiles, by the way, sewn by his ex-wife, who is not considered an artist, and invites the audience to “activate” them. Boyce, declared that “everyone is an artist” and therefore everyone should take a direct part in the creation of a common social body, a public sculpture.

In a speech at the fifth Kassel Documenta in 1972, Boyce said, “So we do not proceed from the means of production, but from the freedom of man as a creative, self-determined being“.

“They should provoke thoughts about what sculpture саn bе and how the concept of sculpting саn bе extended to the invisible materials used bу everyone;

Тhinking Forms – how we mould our thoughts or

Spoken Forms – how we shape our thoughts into words or

SOCIAL SCULPTURE – how we mould and shape the world in which we live;

Sculpture as ап evolutionary process; everyone as ап artist.“

– wrote Boyce in his ‘Introduction’ to Caroline Tisdall’s book on his work (Caroline Tisdall, Joseph Beuys, London and New York, 1979).

Freedom and creativity are the main value and prerequisite for a beautiful social sculpture in which things, money, laws have applied meaning.

Walter, takes the exact opposite position. He creates a complexly organized and tightly controlled process of interaction between people and things, mediated solely by himself, the artist.

Dichtigkeit und Ambivalenz was at the center of a particularly trying day of activations. Walther recorded how a woman insisted on taking “prim steps,” explaining to him that she wanted to move this way “because she thinks it’s her choice. Her mannered movements caused Walther to intervene in the activation of the piece, “since her strained ballet contortions take too much of her attention,” and start the process over. A man protested: “She doesn’t have to follow you. Recalling the confrontation, Walther mused disconsolately in his diary, “Of course not. That someone has to follow me, that nobody has to follow anybody, that I want to make realizations possible; does it have to be said specifically? The visitors wanted to be actors, if not activists, while Walther wanted them to activate the objects.

His clever and numerous objects are designed to mesmerize viewers without giving them any choice. In addition, Walther objects are easy and convenient to put in collectors’ safes and they grow in value nicely.

But what will Boyce tell us?

1.