John Phillips. The role of a poster or slogan is to say to whoever you’re opposing that you’re bigger or more powerful or stronger than someone who is incoherent or not so visible. I think they’re both polarizing and they’re uniting.

Nika Dubrovsky. In other words, your understanding of what a poster is very similar to the project of the Museum of Care, “Fight Club,” which sets up a dialogue between the sides, amplifying both sides’ differences. Thus, the poster is always a dialogue that intensifies the confrontation. Not at all like the dialogues of academics.

John Phillips. It’s not an academic debate. It’s not subtle. It’s actually asking you to take a position and to force you into agreeing or disagreeing.

Сlive Russell. Yes, I totally agree. And that’s what Extinction Rebellion was all about. Movements like Extinction Rebellion are no different. They’re about stand for us, or stand against us – and you must decide quickly because time is running out. This approach forces you to put a stake in the ground.

And Extinction Rebellion was designed to appeal to a very small audience of active activists prepared to put their liberty at stake. A small percentage of the population, but a percentage of the population prepared to go out and do something. It was a call to act now.

Nika Dubrovsky. Thinking about today’s situation, what actions could we take? What posters or messages could we come up with?

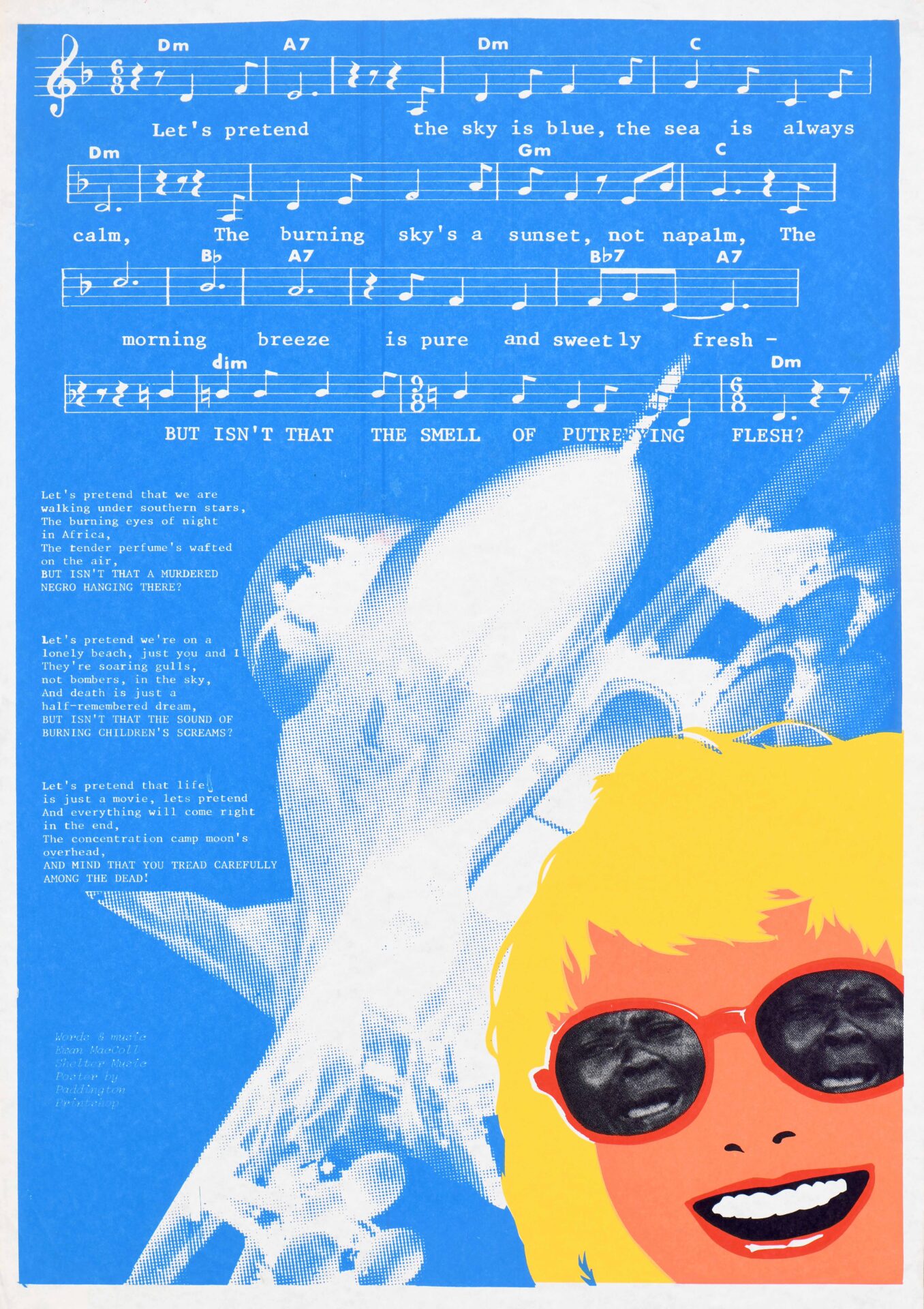

It is interesting to compare Extinction Rebellion’s propaganda technology with the history of protest posters in Britain and with Soviet avant-garde posters, such as the one in our APTART exhibition from the Museum of Unrest collection. It is a remake of Alexander Rodchenko’s famous poster with Lilya Brik, calling people to be literate and love books.

John Phillips. I think you have to think about the cultures. I think posters function strongly within very particular cultures. The Umbrella Rebellion in Hong Kong had really powerful graphics and really strong posters because it was very specific and had a unifying image. The umbrella that people then utilized in all kinds of ways. So you need very easily identified symbols and issues and you also need a culture that is going to want posters. I’m not entirely convinced that we’re in a poster epoch and I think it’s really interesting that Extinction Rebellion has used posters. I thought posters were over to a large degree in the way that I used to make them because people no longer ask me to make them. The other instance where I think posters were really strong was in the Green Revolution in Iran, not what’s going on there now, but previously where the culture was very isolated but had a strong history of graphics and there were some amazing posters created within that. It’s almost as though it was in a Time Warp.

This was during the window of elections in 2014.

Сlive Russell. Yeah, it’s around the same time as the Arab Spring.

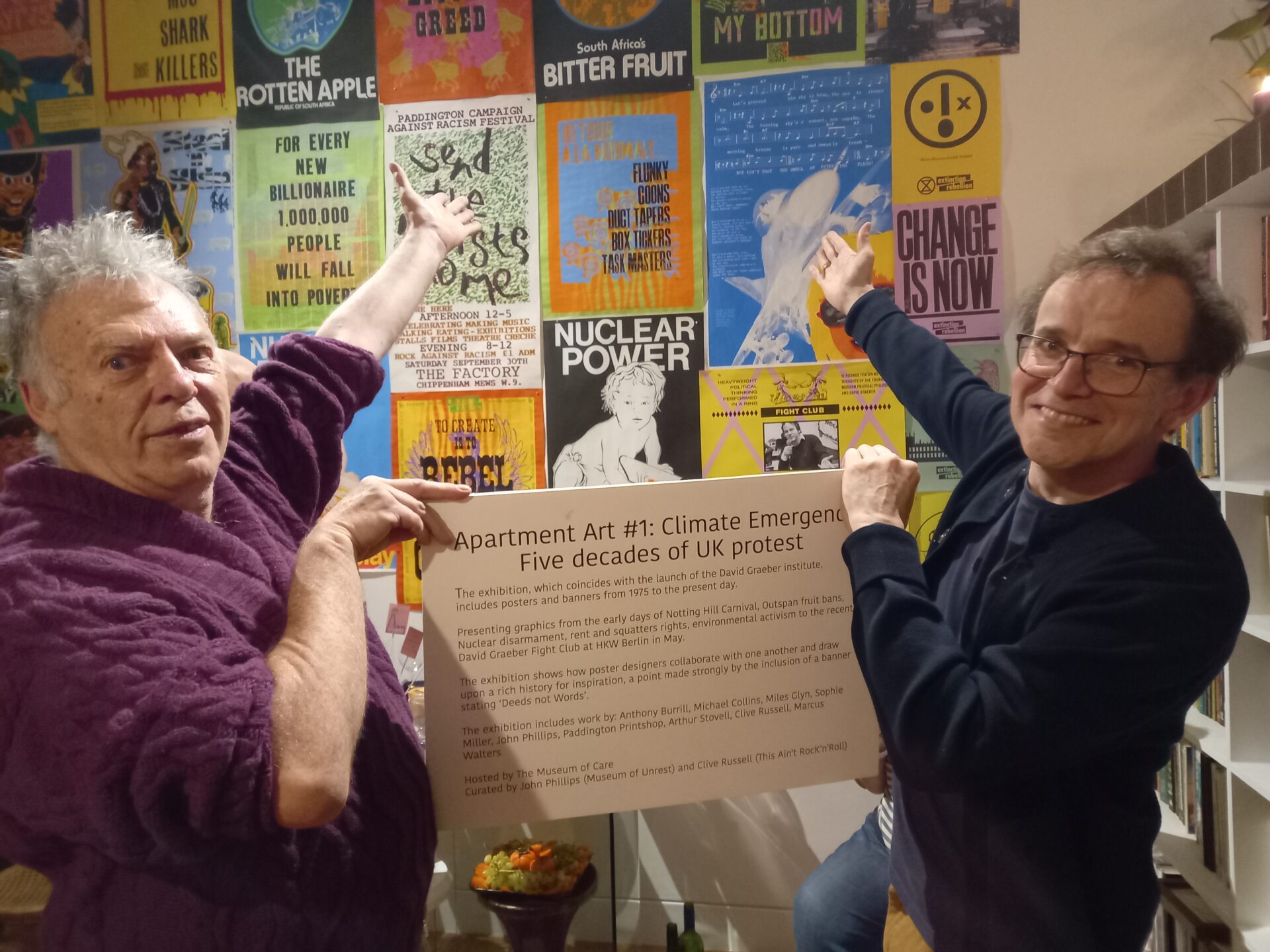

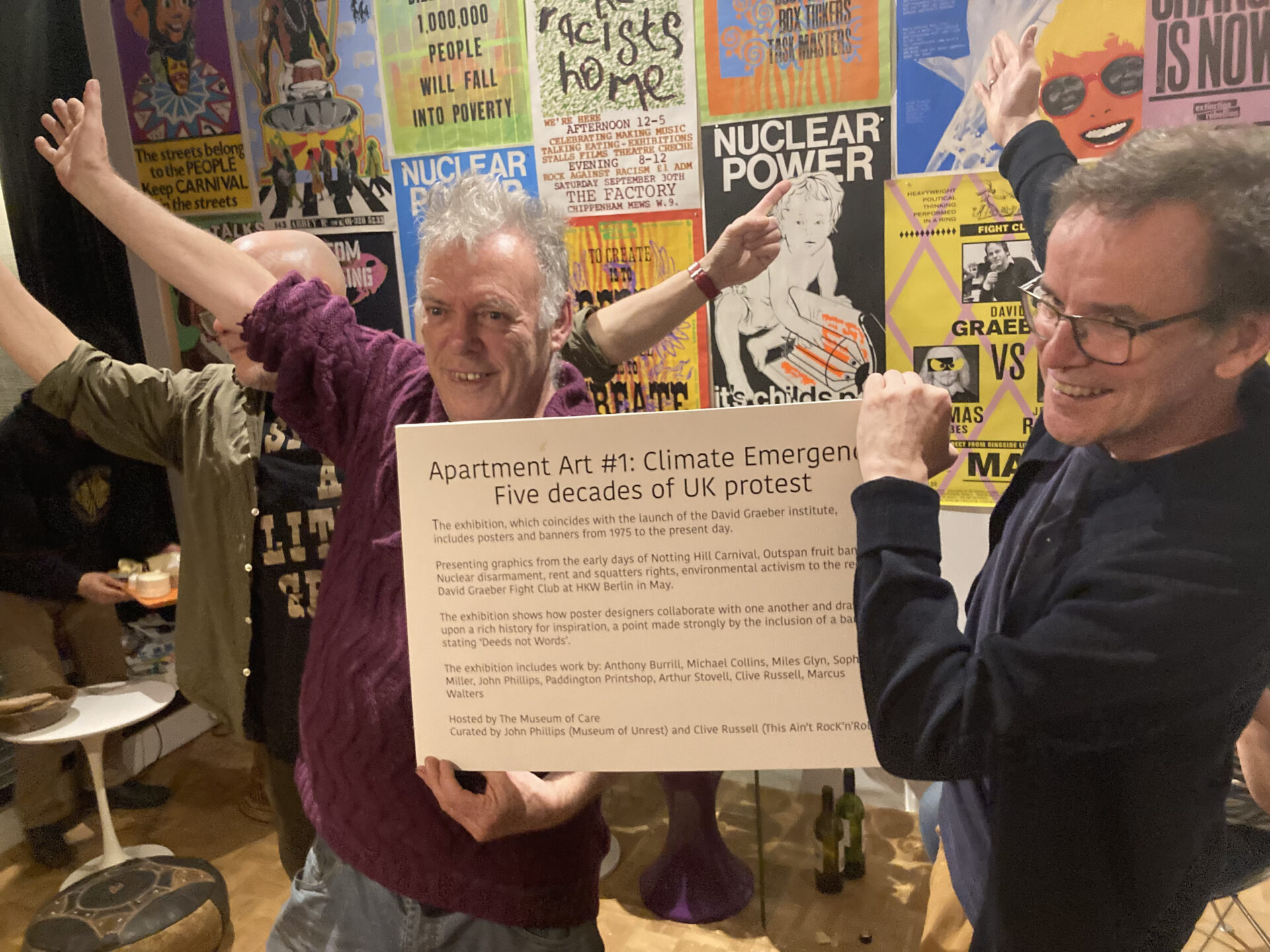

Nika Dubrovsky. Posters are one of the most democratic forms of public art. I am very glad that the first APTART exhibition began with the exhibition dedicated to protest posters.

John Phillips. It’s interesting where they flourish and where other forms take over.

Nika Dubrovsky. Yeah, it’s very interesting. But is it important for your distinction between poster and Street Art?

John Phillips. Posters get put up very immediately and they’re more ephemeral. I was never a muralist because I was dealing with the ephemeral. But then lots of street art gets painted over.

Nika Dubrovsky. This is actually a very relevant question. At today’s APTART dinner, we’re talking about a project called the Brain Trust and I think it has a lot to do with the idea of poster art. Brain Trust is first and foremost a direct action project. We are not going to ask for anything from the powers. We are trying to organize action that is needed and for now more or less everyone understands it. After all, the government changes, but society stays.

The ideology around poster art is much closer to the position stating that the event has already happened and it is time to act. The revolution has already happened for the artists of the Russian avant-garde.

A remade version of Rodchenkov’s famous poster calling on, just think about it: mostly illiterate population of the early 20th century USSR, to buy and read books is on display at our exhibition. For us, Climate Change has already happened. So we are sort of at a zero point. What should we do? I believe, we should not waste our energy trying to convince people to agree with some abstractions, like “Protect nature,” because it is not clear how particular people can protect it if it is being destroyed by giant multinational corporations.

Our task is to find solutions to problems that have to be solved in any case: how to produce food if (unsustainable) industrial agriculture stops working, how to insulate our homes if the temperature outside is too high or too low for humans, how to obtain energy if there is no access to gas and oil.

These are all difficult things to solve, but we have to try.

Сlive Russell. We have similar history in this country. We used to have something called the Central Office of Information, COI? It was set up after the Second World War and was disbanded relatively recently.

One of the interesting things about posters is they set a low bar for allowing people to speak out, break the law. You can put a poster up and if no one sees you do it no one knows you did it. And, when you’re talking about repressive regimes, putting posters up or doing street art is one of the most effective ways of getting people to join in because you probably won’t get caught doing it. Canvas, the group in Serbia who brought down Milosovic. They started by putting up posters. And it ended with them putting his face on a bin. People queued around the block to whack it with a hammer. This simple act toppled him. And that started from putting up some posters, it shows how powerful simple acts can be.

Nika Dubrovsky. The poster campaign in postwar Britain reminds me of the poster campaign in post-revolutionary Soviet Russia. At the moment of serious social change, people need this very distinct type of communication, which is immediate, concrete, vital.

Everything is collapsing, a new life is beginning, and people is trying to figure out how to adapt to this new reality. So I’m sure that the art of posters is essential right now.

John Phillips. What the Bolsheviks needed was a brand. They didn’t think of it quite that way, but they had Constructivism. Malevich lays down the visual language of what becomes constructivism. But for Malevich this is a spiritual thing. It’s about architecture, it’s about spirituality, it’s about icons, it’s got nothing to do with practical material stuff. And his students turn this idea entirely on its head and they use the visual language of Supremacism and turn it into Constructivism which is about material transformation.

Nika Dubrovsky. I think Malevich invents his iconoclastic language to tell humanity that it is free. It is as if the hero of Dostoevsky’s novel The Possessed, the engineer Kirillov, had lived to see the Russian Revolution and become an avant-garde artist. As Bakunin said, “if there is a god, then man is a slave.” Malevich’s universe, although it seems abstract, is incredibly human. That is why he was engaged in suprematist porcelain and planets. His architectural models were created for the people of the future, which, as we know, did appear. They were my parents.

Malevich’s main achievement was to create this amazing democratic language, which could be scaled, changed (his idea of surplus element). Everything in it was prepared for someone to come and take Malevich’s project and make it his own. Unlike the paintings, the beautiful Raphael, which Malevich, by the way, proposed to burn. Malevich managed to reform the visual language, make it democratic.

We also need a democratic language that will help us negotiate directly with each other, understand how to use all these amazing technological advances for the benefit of people and not to their detriment.

If people could speak the language, there would be a chance to somehow negotiate and survive in our post-apocalyptic time. Poster art, as a very democratic form of street art, is ideally placed for this.

Nika Dubrovsky. Just yesterday I was talking to a scientist who is researching cyanobacteria, the oldest organisms on earth, which could feed us all and need neither great investment nor great resources. So much is ready for us humans to solve almost any problem we face.

No one needs to be in poverty, but the system needs problems. Without problems, all business models will crumble.

Сlive Russell. Investment, it’s all about investment. The things we need are things that offer a return on investment – this is what capitalism calls valuable, things that create more capital. But actually what we need are things that save lives, advance our well-being, and help us live together in a better and more equitable way. These are the best investments that we can ask for. But yeah, that’s of no interest to capitalism, there’s no capital created from it, no value for them.

Nika Dubrovsky. Yes, that’s exactly right. So I’m just wondering if it’s possible to organize such a wave of direct action by people, for people, bypassing the logic of clashing with authority. Just bypass it.

John Phillips. I think what’s interesting now is that so many people have printers. So many people have access to a really sophisticated technology and a lot of people make political posters in their bedroom and post them online. But this doesn’t necessarily go anywhere in physical space. Also, a lot of people use a situationist strategy of taking r corporate logos and twisting them upside down. Like I do with the Rotten Apple or a Bitter Fruit . But there is an argument that that only strengthens the corporate image.

The missing element in that approach is images that grow out of popular struggles that people identify as their images and that are not the images belonging to the corporate sector, for example the umbrella which becomes a symbol of the protest. It’s physically there in the protest. It becomes an active agent in that struggle and a unifying symbol but no corporate image dominates it.

If we’re thinking about images and how we make and distribute them we need to address how we fill this gap with images that people will want distributed using technology that they own.

Сlive Russell. Which is a bit like what we did with Extinction Rebellion by giving things away. Allowing people to make things themselves by building on what we’d already done. This subverts branding rather than subtervising existing branding. Subtervising is what John was explaining earlier, when you take someone else’s logo – I certainly agree it can strengthen their brand recognition. There’s some great work and there’s great people doing it, and I’m not going to knock what they’re doing, but I think there’s bigger work to be done in creating actual identities that have their own existence, actually subverting the theory of branding is more powerful, Mai ’68 is an example of that. When you create something that has never been created before. Everything is new then you’re saying something very particular. What you’re saying is ‘away with the old, this is the new,’ this is THE new, this is the zeitgeist and we want you to come and join us because this new thing is something you can be a part of. And this is a much bigger social experiment. And I think the umbrella movement did it amazingly well but it was only in Hong Kong, but it worked a treat because it was just simple and that’s what you need simple motives / messages / asks to build on.

But people were already seriously on the case in Hong Kong. There’s a sunrise here now. I think we’ll see it happening more throughout Europe, people are becoming more aware – we’ve seen it in the States as well. There are going to be thicker lines drawn between groups we’ve seen it happen in the states already – the extreme Republicans and the ‘elite’ Democrats and there’s more difference between the two groups, they’re more polarized. America Great Again exemplifies this, it is another brand created by Trump and injected into public consciousness via conspiracy theories and large scale conferences.

Nika Dubrovsky. What is really needed is a clear language, some recognizable visual code on which to build сollective values. But, there is a general danger of working with brands as a category. For example, the brands of Obama (Hope) and Trump (Make America great again) are different, but the actions are very similar in many ways.

Сlive Russell. It doesn’t really matter about agreeing with this or that. The success these brands have had is the thing people need to think about. And then it’s how do you do something like that and make it successful but for social good rather than for social bad? By giving it a strong social purpose you can unite people (not polarize them). This is like how do you subvert this idea of branding and turn it into something that can actually deliver for people rather than against people? All sorts of brands, all of the brands CocaCola, all of them, all of them are about selling choices, but the choices they sell are meaningless, there is no difference once the choice is made – if it’s CocaCola you just get fatter and use up more water. We need real choices that are not connected to capital but connected to our well-being and the well-being of the ecosystem we belong to.

Nika Dubrovsky. Yes, exactly. Thinking again about Malevich: his language is very abstract (geometric shapes, clear colors) and trade brands do not stick to them. On the other hand, the ideology of Suprematism and Constructivism is very concrete – it is always the production of things and situations that are humansed, that people can use and live better now, not in the future. They have to be functional.

Thus, the political slogans of Stalin’s Russia that gradually replaced Avangard and Constructivists, along with the new architectural style of the Stalinist Empire, called for somewhere in the distant, like “Hope” or “Greatness of the Country.” Stalinist slogans, which appeared after the defeat of the Constructivists, gave rise to the Stalinist architectural style – pompous, undemocratic, referring to abstract greatness.

Сlive Russell. Well, the big thing now is really to look at how we move democracy forward, because that’s the thing that threatens people like Trump and threatens people like Obama and threatens people like Boris Johnson (and all of them really). If we shift democracy forward we can begin positive change. Democracy is stalled. It’s been stalled for years, at least 70 probably more. So how can we shift, start shifting democracy into a new space and begin to talk about how we remove power, how we genuinely remove power from the equation. Can we talk about this is a solution for all our modern problems? Mitigating power, systems that don’t gift power to people? These are the sort of conversations we need people to be getting engaged in. Because it’s actually, at the end of the day, it’s the system we use daily that’s the problem. There’s never going to be equality. There’s no such thing as equality. But the world can be way more equitable.

John Phillips. I think of Christian religion in which for 1000 years or more, 1500 years almost, people believed in a religion whose language they couldn’t actually access. I mean, to sustain a belief system for a millennia in a language that people couldn’t understand is extraordinary. And it tells us quite a lot about the ways in which people can be organized around things that are incomprehensible to them. And I kind of see Fake News and Trumpism as a return to that kind of strange and mystical narrative that is incomprehensible yet organizing. Perhaps we’re doomed by thinking we have to be rational.