Visual Assembly is rooted in the ideas of Cedric Price and Joan Littlewood’s Fun Palace and Alexander Bogdanov’s Proletkult, and I believe it is one of the best things to happen to humanity.

Proletkult: Collective creativity as revolution

Alexander Bogdanov’s Proletkult (1917–1920) created a network of self-governing creative cells, where workers,farmers and even children decided for themselves how to be creative—whether by staging plays, writing poetry, or studying mathematics. He believed that art isn’t a privilege and that the barriers between “professionals” and “amateurs” must be broken.

Bogdanov invited everyone to become co-authors and co-creators of a newly born Soviet culture and science, and surprisingly, many people actually joined together to make it work. By 1920, Proletkult had 400,000 participants—roughly three times more than Lenin’s party.

In small towns, dozens of troupes performed simultaneously, with audiences becoming actors and scripts were written and performed on the spot.

Unlike Lenin, who saw art as a tool for propaganda, Proletkult was the opposite of a top-down power structure. Instead of dictating culture from above, its Houses of Culture functioned as horizontal networks, where local groups decided what to do—whether that meant underground yoga classes or mathematical discoveries. When the Bolsheviks tried to turn Proletkult into a “Ministry of Agitation,” Bogdanov resisted, insisting that real revolution could only happen through self-organization, not government orders.

Though Proletkult didn’t survive past the 1920s, its spirit lived on in thousands of Pioneer Palaces and clubs, where people continued to practice a new way of co-creating culture and knowledge. It had an extraordinary impact—from famous chess players to revolutionary theaters, from musicians to art collectives—’keeping alive’ the very notion of amateur art (samodeyatelnost, or DIY culture) continued to exist.

Cedric Price and Joan Littlewood’s Fun Palace: Architecture as freedom

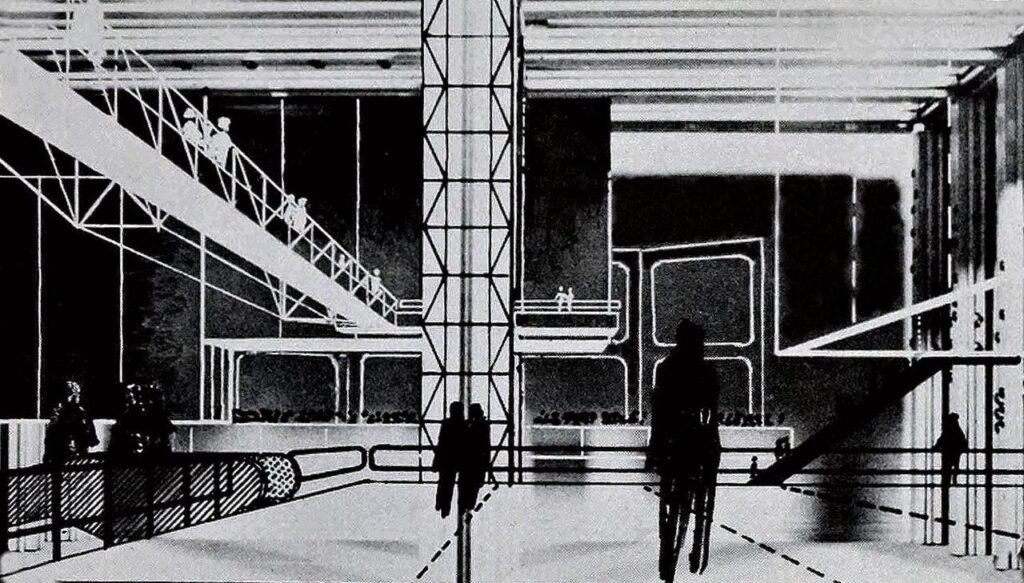

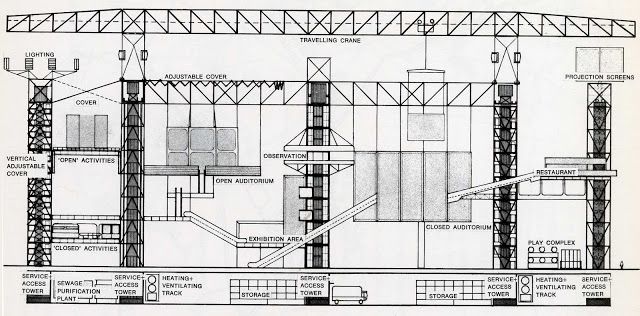

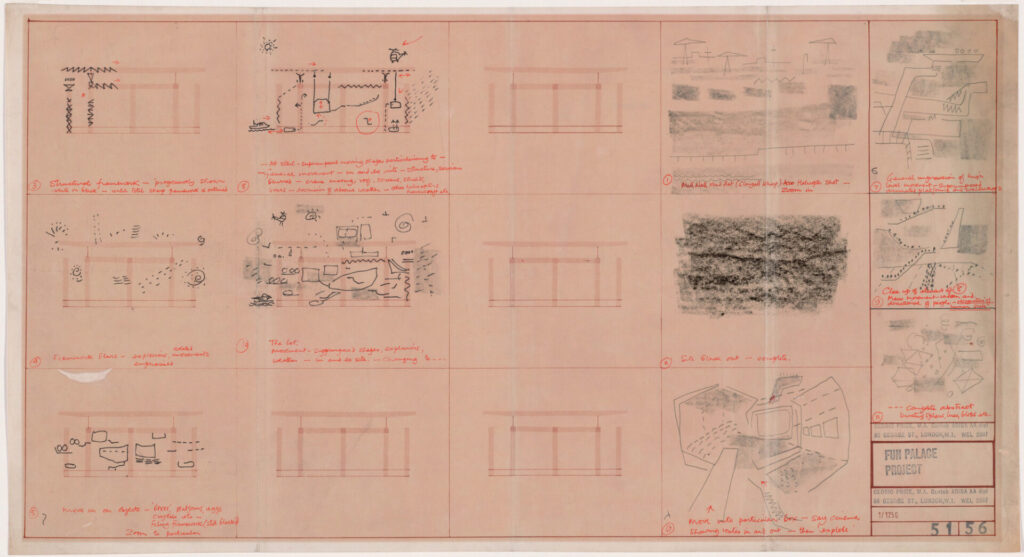

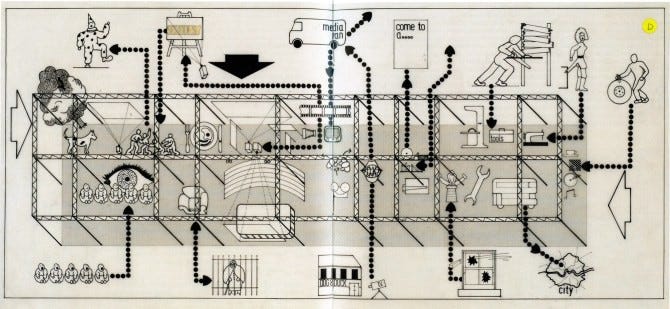

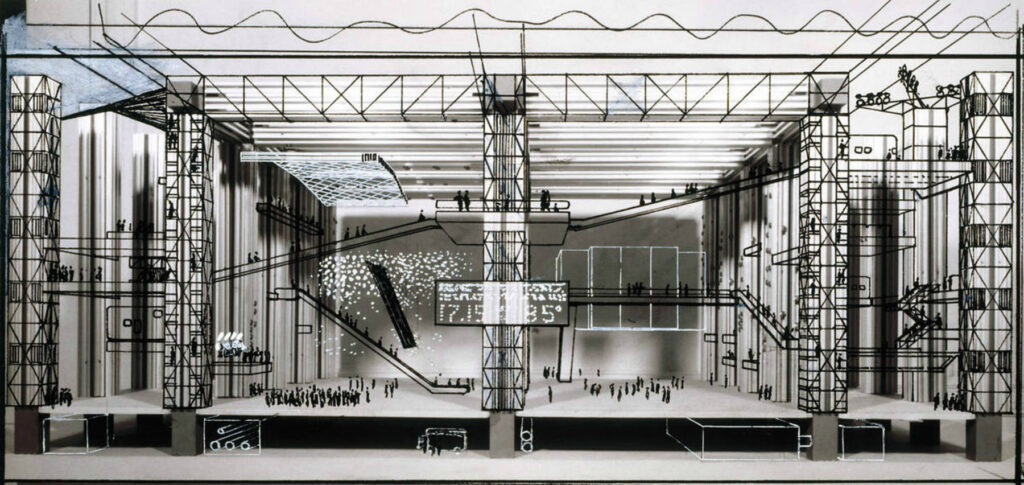

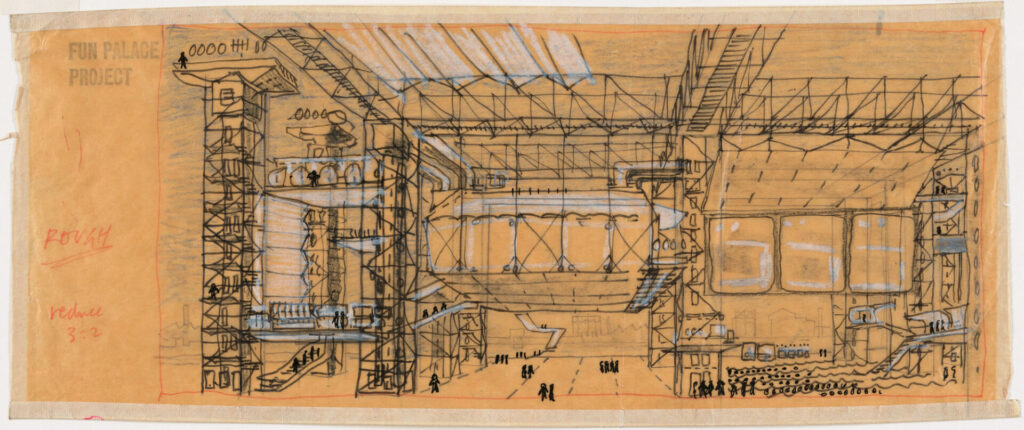

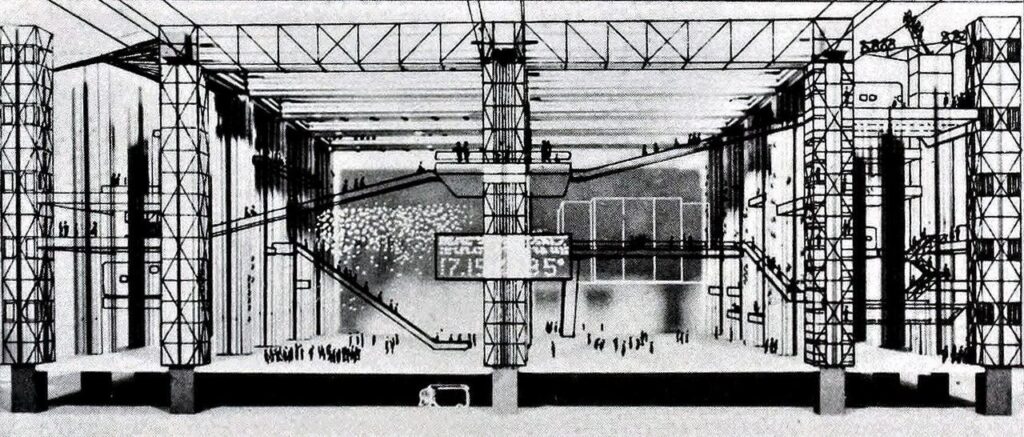

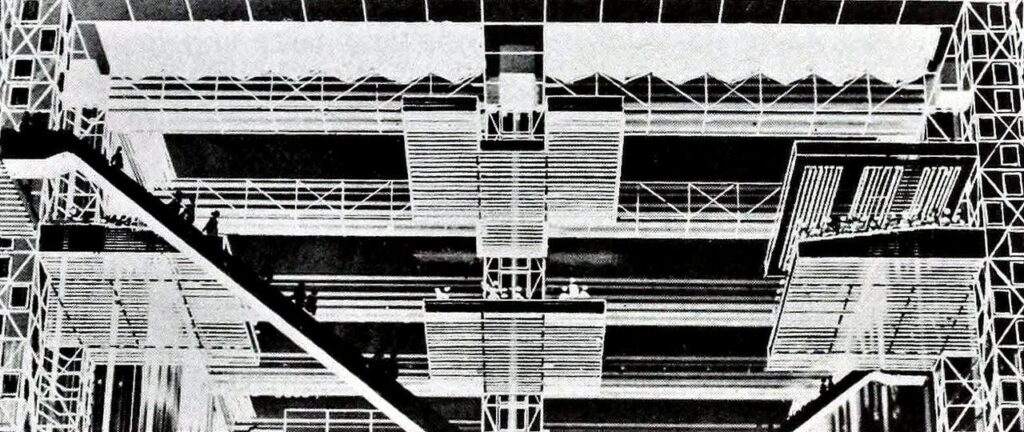

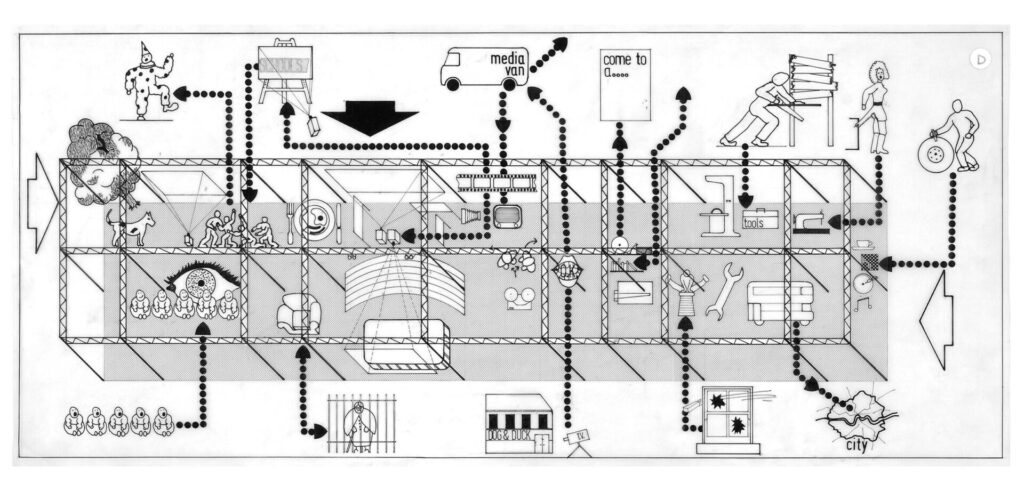

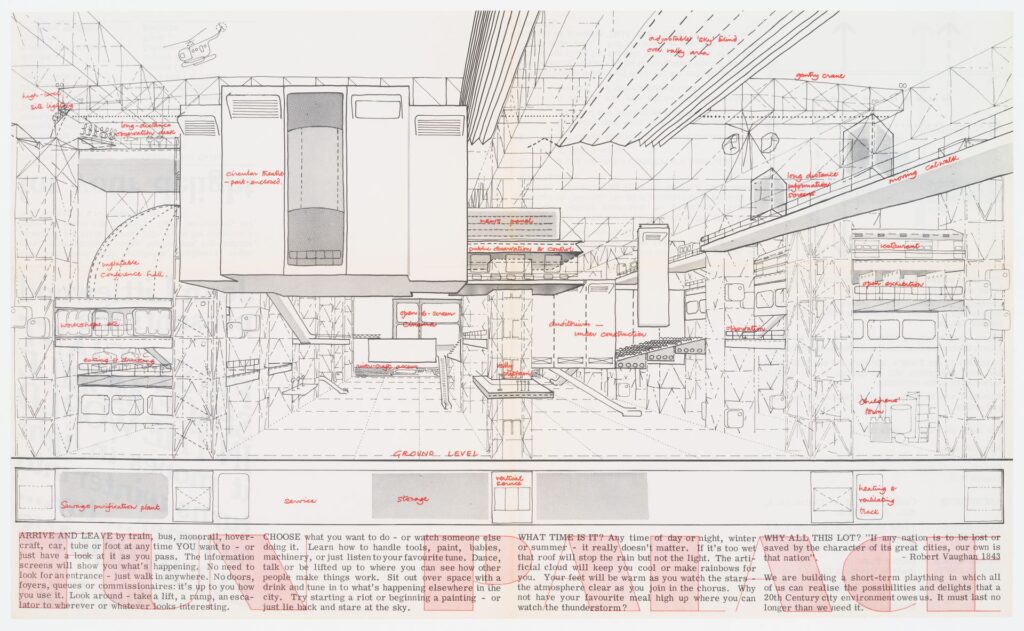

The Fun Palace (1962) was an architectural manifesto for democracy in action. Instead of an unchanging structure—a frozen expression of the architect’s vision of beauty, history, or whatever else great architecture is supposed to represent—Price and Littlewood imagined a flexible “machine for people”, where space adapted to its users. No fixed stages or galleries—just modular units, moving platforms, and open areas that could be reconfigured according to people’s needs. Want to make a movie? Go ahead. Need a welding workshop? Do it. The idea was to erase the line between “performers” and “audience,” giving everyone equal rights to create culture through collaboration.

Even Price’s sketches show crowds deciding how to use the space—whether for theater improvisations or political debates.

Everything was built on trust in human agency. The architect doesn’t impose a scenario; they provide a framework for experimentation—like a massive real-world Minecraft.

Visual Assembly: How can we make utopia work?

Though separated by decades, all three projects share a core belief: that a social framework can empower people to understand, create, and reshape their environment.

Like The Fun Palace, Visual Assembly is an open, participatory system—more a process than a fixed structure. It operates as a playground, where visual tools serve as evolving platforms for dialogue and decision-making, rather than static representations. Just as Fun Palace rejected rigid hierarchies in favor of dynamic interaction, Visual Assembly invites users to actively shape meaning through collective engagement.

Both concepts break away from institutional authority, shifting people from passive consumers to active participants. By decentralizing knowledge creation, they transform spaces into arenas of improvisation, exploration, and co-creation—true playgrounds of possibility.

All three projects understand that they are not inventing anything new. They simply help people to realize what they know already: we all love creative solidarity and have an innate desire to make things together.

Playground as a revolution

A playground is never just for children—adults come too, watching over them, talking and connecting with one another.

The playground is a deeply political space, mirroring shifts in public life. The French and Russian revolutions began with the symbolic act of turning royal palaces into museums—the Louvre and the Hermitage—as a method to transfer power from kings to citizens. But what if, instead of seizing palaces, revolutionaries had seized playgrounds? What if, instead of placing power in the preservation of art and historical treasures, they had built an infrastructure of free, safe, and public learning and play spaces across the country?

In a way, this is what the Russian Proletkult attempted in the first years after the Revolution—before Stalin crushed it. But even today, we still feel its influence. Palaces of cultures that Proletkult set up in the early years of the Russian Revolution still exist and function, teaching kids and adults. math, chess, art and so on. The question remains: what type of revolution can begin, not through barricades and institutions, but through the radical act of making play accessible to all?

Colin Ward described the adventure playground as a kind of utopia in miniature—a society in its early stages, with tensions and spontaneous harmonies, diversity and cooperation, an organic and unforced balance between individual creativity and communal life. Unlike traditional playgrounds, which impose rigid structures and predetermined play, adventure playgrounds allow children to shape their environment freely, to evolve from exploration to discovery to creativity.

But why should this stop with childhood? Do we accept the paradox of free imaginative youth followed by a lifetime of unfulfilling labor in adulthood? If adventure playgrounds are spaces for self-organized play, shouldn’t we also create their equivalent in the adult world? Shouldn’t every public space encourage experimentation, improvisation, and collective action?

At the heart of each playground will be a Visual Assembly—a space where people can gather and reinvent how to reinvent and rebuild their surroundings. Not just the playground itself, but other social spaces as well—hospitals, schools, public squares, any place can be reimagined.

The rest of the playground will be designed for open participation: from invited artists creating installations with water, sound, or flags, to local residents building giant chess sets or planting trees—or whatever else they can imagine. Ideally, this space will inspire projects that provoke collective creativity—whether through theater stages or the construction of a shared labyrinth—just like in Proletkult or Fun Palace.

But every community, every space must decide for itself.

Protective mechanisms: On defense, survival, and resilience

It is deeply frustrating that one of these projects (Fun Palace) was never built, and another (Proletkult) was brutally interrupted by short-sighted people. It’s impossible to imagine how different our world could have been if these ideas had fully taken root in society.

Utopia literally means a place that does not exist. The implication is always that some naive dreamer imagined a beautiful but unrealistic vision.

But what if, this time, we build a framework for collective creativity that doesn’t only survive for a year or two—but spreads everywhere and stays with us forever?

Strategies for infiltrating public space

How do we embed Visual Assembly into everyday life, making collective creativity an integral part of our public spaces? The answer could be infiltration—not through grand institutional reforms, but through small, accessible interventions that anyone can initiate without requiring funding or permission.

One of the simplest and most effective strategies is collective workshops with children and local communities to imagine what a playground can be. A few pieces of chalk, some cardboard, and an open conversation are enough to sketch out the possibilities. These workshops require no official approval, no budget—just the willingness to gather, observe, and rethink the space together.

A Visual Assembly playground is not only a playground—it is a map of care, a dynamic system where the act of building and maintaining space becomes a form of collective responsibility. Instead of seeing public space as something designed for people, it is about creating spaces with people—shaped by what they need, hope for, and imagine.Every playground, every square, every park holds the potential to become a site of continuous reinvention—a true experiment in collective care and creative autonomy.

Futher reading: Another Art World, Part 3: Policing and Symbolic Order by David Graeber and Nika Dubrovsky