Soviet ideas of large-scale public spaces created by artists have their roots in the best-known modern utopia, Tommaso Campanella’s Sun Cities, which inherited the writings of Thomas Moore and, in turn, Plato’s Republic.

The walls of Tommaso Campanella’s utopian “City of the Sun” were painted with educational murals, and the entire city became a school where children were walking around led by a teacher. The same idea formed the basis of Lenin’s monumental propaganda in the USSR.

“You remember, Anatoly Vasilyevich, – Lenin asked Lunacharsky (Minister of Education), – that Campanella in his ” Sun State ” says that on the walls of his fantastic socialist city is painted with murals, which are a visual lesson for young people in natural history, history, excite civic feeling – in short, are engaged in the education of new generations. It seems to me that with some modification this could be adopted and implemented by us now. In various prominent places on suitable walls or on some special structures for this purpose, one could scatter brief but expressive inscriptions containing the most enduring fundamental principles and slogans of Marxism, also, perhaps, firmly constructed formulas giving an evaluation of this or that great historical event.”

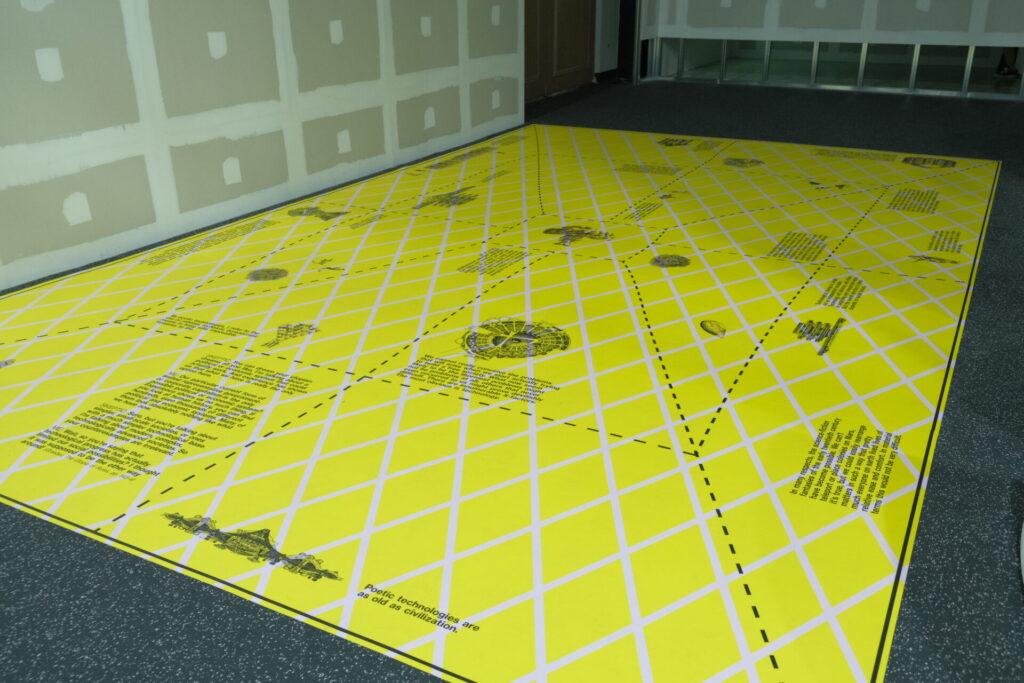

The project Visual Assembly is built on the idea of monumental propaganda and understands the common space as educational, but it turns wall paintings into floor paintings and propaganda into a space of dialog.

The task of the artist does not seem to be to work as a TV set – to broadcast, teach and instruct, but rather to organize horizontal spaces of equal communication between all participants.

Visual Assembly is an opportunity and an invitation to dialog, it is practice, not an object. I try to organize as much space as possible for participants to draw and write on their own.

I have organized Visual Assemblies in different countries in Cuba, Ukraine, Iceland, Germany, Russia and England. It is usually easy to work with children.

Perhaps because they readily go along with a proposal to re-plan the future of their city, school, or the world. Adults, trained that nothing can be changed or that change only leads to disaster, are harder to sway into collaborative discussions. Besides, there are very few of us who have experience with collective creative action.

But this is what the Visual Assembly would like to contribute to! Its aim is to offer an experience of collaborative planning of our social spaces.

This visual assembly is dedicated to the theme of Technology as social relations, following talks with Cory Doctorow and accompanying video installation “Fight Club”, which reflects on different ideas of human nature.

If technology is not a thing in itself, not a magic formula, but a tool that allows us – humans – to realize our ideas about how our social space should be arranged, then it would make sense to talk to each other about what kind of world we want to live in.

Perhaps then we will create technologies that reproduce human life rather than killing it.

As an invitation to dialog, Visual Assembly offers quotes about technology and utopias from David Graeber.

Here they are:

DYSTOPIA TEXTS

The Internet is surely a remarkable thing. Still, if a fifties sci-fi fan were to appear in the present and ask what the most dramatic technological achievement of the intervening sixty years had been, it’s hard to imagine the reaction would have been anything but bitter disappointment. He would almost certainly have pointed out that all we are really talking about here is a super-fast and globally accessible combination of library, post office, and mail order catalog. “Fifty years and this is the best our scientists managed to come up with? We were expecting computers that could actually think!”

It seems for the moment at least we have reached a point where disappointment with childhood dreams has become institutionalized. If they are realized, they are realized in a virtual realm, as simulations. Is it any wonder, then, that we are surrounded by philosophers telling us that everything is simulation and that nothing is really new?

In this final, stultifying stage of capitalism, we are moving from poetic technologies to bureaucratic technologies.

What technological progress we have seen since the seventies has largely been in information technologies-that is, technologies of simulation, the ability to make imitations more realistic than the original.

What the Internet has really brought about is a kind of bizarre inversion of ends and means, where creativity is marshaled to the service of administration rather than the other way around.

Just as the invention of new forms of industrial automation in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries had the paradoxical effect of turning more and more of the world’s population into fulltime industrial workers, so has all the software designed to save us from administrative responsibilities in recent decades ultimately turned us all into part or full-time administrators.

Meanwhile, the greatest and most powerful nation that has ever existed on this earth has spent the last decades telling its citizens that we simply can no longer contemplate grandiose enterprises, even if—as the current environmental crisis suggests—the fate of the earth depends on it.

Meanwhile, in the few areas in which free, imaginative creativity actually is fostered, such as in open-source Internet software development, it is ultimately marshaled in order to create even more, and even more effective, platforms for the filling out of forms. This is what I mean by “bureaucratic technologies”: administrative imperatives have become not the means, but the end of technological development.

What the Internet has really brought about is a kind of bizarre inversion of ends and means, where creativity is marshaled to the service of administration rather than the other way around.

…it might be interesting to ask oneself how much the technologies of information are themselves part of the apparatus of violence, essential elements in ensuring that small handful of people willing and able to break skulls will always be able to show up at the right place at the right time. Surveillance, after all, is a technique of war, and Foucault’s Panopticon was a prison, with armed guards. (Graeber, ‘Provisional Autonomous Zone,’ in Possibilities, pp. 175-6; also in Lost People, p. 26)

Even if you agree that for whatever reason, while a wide variety of economic systems might once have been equally viable, modern industrial technology has created a world in which this is no longer the case—could anyone seriously argue that current economic arrangements are also the only ones that will ever be viable under any possible future technological regime as well?

Modern factory discipline was born on ships and on plantations. It was only later that budding industrialists adopted those techniques of turning humans into machines into cities like Manchester and Birmingham. One might call pirate legends, then, the most important form of poetic expression produced by that emerging North Atlantic proletariat whose exploitation laid the ground for the industrial revolution.[1] (Graeber, Pirate Enlightenment, p. xvi)

While almost all the technologies children in 1900 imagined would exist by 1950, that were the stuff of science fiction at the time—radios, airplanes, organ transplants, space rockets, skyscrapers, moving pictures, etc— did in fact come into being more or less on schedule, pretty much none of the ones children born in 1950 or I960 imagined would exist by 2000 (anti-gravity sleds, teleportation, force fields, cloning, death-rays, interplanetary travel, personal robot attendants) ever came about.

Certainly, poetic technologies almost invariably have something terrible about them; the poetry is likely to evoke dark satanic mills as much as it does grace or liberation. But the rational, bureaucratic techniques are always in service to some fantastic end.

In this final, stultifying stage of capitalism, we are moving from poetic technologies to bureaucratic technologies.

UTOPIA TEXTS

There is very good reason to believe that, in a generation or so, capitalism itself will no longer exist-most obviously, as ecologists keep reminding us, because it’s impossible to maintain an engine of perpetual growth forever on a finite planet,

and the current form of capitalism doesn’t seem to be capable of generating the kind of vast technological breakthroughs and mobilizations that would be required for us to start finding and colonizing any other planets.

There’s nothing wrong with utopian visions. Or even blueprints. They just need to be kept in their place. The theorist Michael Albert has worked out a detailed plan for how a modern economy could run without money on a democratic, participatory basis. I think this is an important achievement—not because I think that exact model could ever be instituted, in exactly the form in which he describes it, but because it makes it impossible to say that such a thing is inconceivable.

In the 1950s and 1960s, it was assumed by now we would have computers with whom we could carry on a conversation, or robots who could put away the dishes or walk the dog.

It’s becoming increasingly clear that in order to really start setting up domes on Mars, let alone develop the means to figure out if there actually are alien civilizations out there to contact — or what would actually happen if we shot something through a wormhole —we’re going to have to figure out a different economic system entirely.

All those mad Soviet plans—even if never realized—marked the high-water mark of such poetic technologies. What we have now is the reverse.

It’s also true that in actual play, there are no rules; the books are just guidelines. The numbers are in a sense a platform for crazy feats of the imagination, themselves a kind of poetic technology.

Bureaucracy enchants when it can be seen as a species of what I’ve called poetic technology, that is, one where mechanical forms of organization, usually military in their ultimate inspiration, can be marshaled to the realization of impossible visions: to create cities out of nothing, scale the heavens, make the desert bloom.

These fantasies are cathedrals, moon shots, transcontinental railways, and on and on.

For most of human history what I’ve called poetic technology, this kind of power was only available to the rulers of empires or commanders of conquering armies, so we might even speak here of a democratization of despotism.

Let our imaginations once again become a material force in human history.

If we’re going to actually come up with robots that will do our laundry or tidy up

the kitchen, we’re going to have to make sure that whatever replaces capitalism is based on a far more egalitarian distribution of wealth and power—one that no longer contains either the super-rich or desperately poor people willing to do their housework. Only then will technology begin to be marshaled toward human needs.

By poetic technologies, I refer to the use of rational, technical, bureaucratic means to bring wild, impossible fantasies to life.

If the ultimate aim of neoliberal capitalism is to create a world where no one believes any other economic system could really work, then it needs to suppress not just any idea of an inevitable redemptive future, but really any radically different technological future at all.

SKEPTIC:You can dream your utopian dreams all you like, I’m talking about a political or economic system that could actually work. And experience has shown us that what we have is really the only option here.

ME: Our particular current form of limited representative government-or corporate capitalism-is the only possible political or economic system? Experience shows us no such thing. If you look at human history, you can find hundreds, even thousands of different political and economic systems. Many of them look absolutely nothing like what we have now.

SKEPTIC: Sure, but you’re talking about simpler, small-scale societies, or ones with a much simpler technological base. I’m talking about modern, complex, technologically advanced societies. So your counterexamples are irrelevant.

ME: Wait, so you’re saying that technological progress has actually limited our social possibilities? I thought it was supposed to be the other way around! (Graeber, The Utopia of Rules, pp. 143-4)

We cannot really conceive the problems that will arise when we start actually trying to build a free society. What now seem likely to be the thorniest problems might not be problems at all; others that never even occurred to us might prove devilishly difficult. There are innumerable X-factors. The most obvious is technology.

Poetic technologies are as old as civilization.

In many respects, the science-fiction fantasies of the early twentieth century have become possible. We can’t teleport or place colonies on Mars, it’s true, but we could easily rearrange matters in such a way that pretty much everyone on earth lived lives of relative ease and comfort. In material terms this would not be very difficult.

Technological change is simply not an independent variable. Technology will advance, and often in surprising and unexpected ways. But the overall direction it takes depends on social factors.