Here is our first dialog. Lets us know what do you think!

N&P

Tell us about yourself, where do you live?

Jai

I’m Ahmad Sujai from Jatiwangi Art Factory, a project started in 2005. I’m the director of JaF from the 2021 till 2022 period. I live in Majalengka City.

N&P

So it’s already almost seventeen years. And how many people live there now?

Jai

It’s almost forty people but some people don’t live there because there are married couples inside our group and after two years spent inside JaF they must move to their own house. It’s a challenge for a young married couple to manage to have their own house, and JaF offers them the possibility to share the place for two years. Some have moved to other places but are still working there: this process is just about living, to be able to move in order to be independent.

N&P

Can you tell us how the work, the life, the outside and the inside related to each other in JaF?

Jai

We are working in Jatiwangi district, one district with sixteen villages there. And we are also working in Jatisura village, in the Jatiwangi district. We are working in JaF and also, as I’ve mentioned before, we live in other places. We have conceived this way of living and working because the Jatiwangi Art Factory is not just a collective, we consider ourselves also as a family: we are always connected to each other, even if we do not live there.

We are essentially a family. We are not just working together every day, we have conversations, we have fun together. We are not only talking about serious work-related things all the time, but also about how we can arrange our families and facts about daily life. And just then we are talking about the important things, like running the open kitchen, a place where all the people can eat together: we share the food, as well as the gas, with the people who live there and with the visitors or guests, so we can always eat together there.

N&P

Tell us more about the details of your daily life: where do you get your food?

Jai

We are cooking together. We grow our own food in the back of our place. Some plants, like chili for example, but we are also working outside JaF in order to make money, so we can buy our food. Each person has their own job: someone is doing photography, someone graphic design, someone web design. And then we set up the amount of money we want to share with the community in order to run the organization. Because, like I’ve already said, we are a family. We are not a company and we are working with and for the community. That’s why we pay the community. It’s not the community that pays us.

N&P

What are you cooking together?

Jai

Indonesian food always, like tofu, tempeh, sambal – that is like a chili sauce- soup, every day.

N&P

Who is taking this cooking responsibility? How do you divide it?

Jai

We invite people from our neighborhood to cook in our kitchen, because they are also part of our family. And then we pay them for cooking, every month. There is a rotation in the cooking shifts in our place, in order to share our money with more people from the neighborhood.

N&P

How do you connect to people outside of Indonesia? Now you’re part of the global art system because you are part of documenta: how it all happened?

Jai

We have been connected with the people outside of Indonesia since the beginning of our community. One of our founders – Arief Yudi and Ginggi Syarief Hasyim – studied art. Arief Yudi and his wife have studied art, but Arief Yudi has not finished because he made connections before around Indonesia and then internationally. And when Arief Yudi came back to Jatiwangi in 2004 or 2003, he started to think about making his family place a kind of art space or cultural space, and talking with his brother Ginggi, who already had connections with the local people in Jatiwangi and around Majalengka City, the first connection has started. In the beginning we got to know the people from the district and after that we explained to them what we were doing. In our place there are no art institutions, we don’t have an art audience: that’s why we like making happenings suddenly, like on the street, sudden performances which are something strange for the local people and then make the local people surprised by what we are doing. We share these experiences, and people understand. And after these first happenings we made a TV community and a radio community. In this case the important thing is not just the media: in the radio station we’re making every week an invitation to the people from the neighborhood, so that they can come in and have a karaoke session, and after talking together and share with them what we are doing. And then also in the television community we invite people to make videos. We share the knowledge on how to make the video. Before it was not like now, when everyone can make video with a smartphone, so we showed them how to use a camera, and in this way the neighbors make the news directly from their place: What is the neighbor doing? Like, for example, what are you cooking today? And then they share those videos with the people in the TV community. We have a signal for one district, for all the Jatiwangi district, that we use to make people know what the neighbors are doing, because the people in the village already are aware of what the celebrities are doing, but don’t know anything about what their neighbors are doing. It was the first idea to get to know each other around the Jatiwangi people.

N&P

Now you also travel through the West a little bit. Can you tell me if, from your point of view, is there a difference between the Western understanding of what art is and yours?

Jai

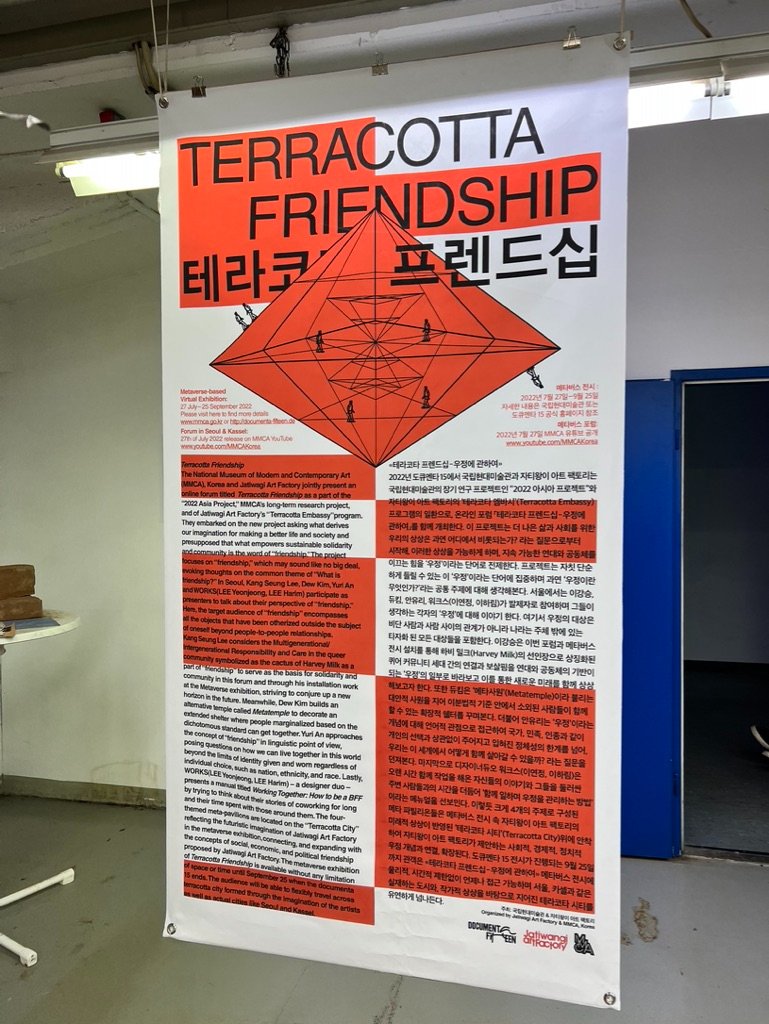

For me art is like daily life. In daily life we also see art in the communities. For example, in Indonesia we have done installations using the lines for hanging clothes, and the people already know about that but didn’t know that this it’s an art installation. Art can also use something like that as an artwork, since the installation has a narration, but it’s very difficult to explain how the West’s perspective on art is different from our perspective on art. When we come to Germany, most of the people see art as masterpieces, very beautiful pieces, etcetera, but what we are bringing here is not something like that. We are bringing something that can be defined as more conceptual. We are bringing what we need in our daily life, and what we want to do in the future. For example, we are bringing here our long term project, for which we are working together with the government, the new identity of our city called Kota Terrakota, that means Terracotta City.

N&P

Can you tell us more details about that project?

Jai

We had an agreement in 2019 and we are doing a biennial, called Indonesian Contemporary Ceramic Biennial, where we invited our governor to come and we presented our idea about changing the identity of the city.

N&P

How do you intend to change it? How was it before and how do you envision it to be?

Jai

We have a long history and tradition rooted within the rooftop production and the roof tile factory and we are seeing that our place is now changing, since a lot of investors are coming, such as Nike and Adidas factories, as well as a lot of textile factories from Taiwan and China, changing our landscape, our culture and then the people also. It’s not about talking about how happy the people from the local area are: we are thinking about the future, about how to live a better life, because the tradition we have of working with the traditional factory it’s different from the impact of the modern factory. The culture of the factory is different: for example in the rooftop factory we can bring our kids there so they can stay there while their mothers are working, but in the modern factory the mothers cannot bring their kids with them and the children are left alone at home, or with grandparents, creating a gap between the kids and the mothers, and for me that’s the problem.

N&P

It’s also a separation of private and public life. That’s what all capitalism is about: you go to work and then you return home. Can you describe more how the traditional factories in your town will arrange, so that the kids will be able to be around when their parents are working and what else?

Jai

The children can also play there and then learn how people in Jatiwangi do some activities connected to the soil, in this way it’s possible to keep on seeing what we are doing in the factory, seeing how connected are the people with the soil to make roof tiles, for example. It’s important for the kids to know what happens in the traditional factory.

N&P

And these traditional factories now are owned by the wealthy local citizens but now the international corporations are coming, taking this conveyor type of work, am I right? Do you think it’s reasonable to think that you’ll be able to change the way it’s developing?

Jai

I think it’s important to introduce to the people the fact that we have a tradition, and that’s the reason why we are talking with the government: it is important to change our city identity to share this knowledge with the people, this long tradition with soil doing roof tiles and that’s why we imagine to change our city identity with the Terracotta roots, making the Terracotta City, for this new identity. After this dialogue we had an agreement, we made a signature for an agreement with our governor. Then after that, our governor gave us the project for the design of a new city square, in order to make a new city square in the center of the city. After this agreement the local government was kind of in a rush because the order to make a new city square was from the provincial government. Using terracotta it’s important for us because our product can also be part of this development project. After that the local government in the city also wanted to talk with us, because before we only had a plan to make this city identity only in our district, but the local government in the city proposed us to make it for all of Majalengka City, with a new policy in which it is declared that 30% of terracotta material must be used in every new building in our city, even if the building is a new factory. After that we agreed to work together to build our city.

N&P

Amazing! So you just went straight ahead to the government policies. If you would be able to do whatever you want, what other policies would you change in your system?

It looks like you successfully implemented a new policy, a new design policy for the city. If you would be able to implement more, what else would you do? You were talking about textile factories that now will be turning into mass production. How did they function before?

Jai

We are also thinking that if we are changing the identity of the city, we can imagine not only the development of the building, but we can also develop an education program for the future, an environment for the future. That’s why we made the project – after Terracotta City – called Terracotta Embassy. We want to connect with international friends by making an embassy, not from government to government, but from people to people. That’s why now we have cooperation with four countries, such as Switzerland and Taiwan. The collaboration with Taiwan is already running. We have also focused on the meaning of the embassy, because each country must have a specific focus to support our city identity. The Taiwanese friends from Suave art have a focus on ecology and economics, for example. The embassy function is a kind of laboratory, a research place to investigate on how to make our city more ecological, more sustainable, talking also about the economy and the future, while with the Switzerland embassy we have focused on education, on how we can do education for the future. We have planned to build a university. We have a collaboration since two years ago with the University of Technology in Bandung who will build a new university in Majalengka. This big institution from the university talked with us even before than with the government about their intention to build the university in our city. Maybe now we are even stronger than the government. They invited me to come to the university in Bandung, and we talked: they have a study course related to the machines, which can support our traditional knowledge in making terracotta, but mixing it with technology. That’s the reason why we agreed: they give us something more sustainable through technology.

N&P

Why do you think they’re doing that? Is this commercial? How does it work to build a university? It’s a lot of money, probably.

Jai

We’re just thinking of making a university in Majalengka because we want to give the next generation a better life in our city. People from our local community have always studied in other cities, maybe because they don’t really agree or don’t really like to study in our place, maybe it’s better to study in a big city. That’s why we’re just thinking that we must make a university so the next generation can also have the possibility to study in our city, and compare it with universities in big cities.

N&P

What I’m asking is something else: everywhere in the world education is privatized. And in Europe, previously in the UK, before you didn’t need to pay to study, but now you have to pay more and more. In the US it’s a total disaster. I’m just trying to understand why and how these people are coming. I don’t understand where money is coming from.

Jai

With Switzerland we have cooperation with the member of FOA-FLUX, from one of the professors teaching in the Zurich University of the Art, in a way in which we can also have exchanges between Majalengka people and also for the Switzerland people to study and learn from each other.

N&P

So that means you’re dealing with educational institutions that are outside of the commercial realm.

Jai

We are also just thinking about the fact that studying in the university is very expensive now in Indonesia, especially in the university and in the college. Senior high school is gratis, but the university is very expensive and if you don’t have good scores it’s very hard to study in a good university.

N&P

How would your university be? Will you charge money for this new university? How would financially look?

Jai

We are just thinking and discussing how to manage the university in the future because it is still a plan to build the university, as well as how to deal with the financials: it could be an open study course, not very expensive, it’s a project for the next generation.

N&P

Amazing. Can we ask you what is your favorite work in Documenta?

Jai

It’s difficult because for me all of the documenta works now are kind of the experience of sharing knowledge from every country in the world with their different methods and different practices. I cannot choose one because every work gives me some suggestions to think about what we can do for our place. For example in Mali – because I have been there before to make a research field trip – I was surprised because when Festival sur le Niger is on, I see a lot of people with fancy stuff coming, but in the daily life we just see the people on the street selling something… so it’s a real change that comes from Festival sur le Niger, for the people and the area: they are involved in the economy, during the festival season there are a lot of people selling things, open stores. It was quite amazing when I saw what happened during Festival sur le Niger.

N&P

You went there because you share the same venue at this documenta. Where is it located?

Jai

In our space in the Hübner areal. I visited them before the beginning of documenta, in order to see what happens during the Festival. We share the same space, so we arranged our exhibition together.

N&P

You said that the work that you were doing with the local people in your village and in your city is about daily life but you defined it as conceptual. Can you tell me more about that? How it happens that daily life suddenly leads you to use the term “conceptual”, that for the West usually refers to something outside of daily life, quite the opposite.

Jai

I think that also in the West “conceptual” refers to using daily life things in an artistic way, but we bring what we are doing in our daily life, for example, we work with the rooftop factory and so we are also bringing it here in a way that it’s not too different from our situation in our local life.

N&P

So imagine that Indonesia and your particular town would develop exactly as you planned and then you will have lots of universities, art spaces and so on. How would it be different from what we have in the West, from your idea? How would you build it? Would you build it similar to what you see in the West? Would it be a little different, and if so, in which way?

Jai

For me, in the West, I see that some universities here are cheaper also for the taxes and fees, but I’m just still wondering why studying in the West is cheaper than in our place. I’m also curious about how universities deal with finances and I want to learn about that, since in our place it’s very expensive to study.

N&P

I think it’s very expensive to study in the US. For example, it’s $100,000 a year or something like that. If you talk about European countries like Germany it is money from the government that still keeps investing money in this but in the UK since some years they don’t do it anymore. In Argentina, as far as I know, it’s free and there are no exams, so anybody can sign up and study. The professors are proud of teaching there, and if too many students sign up for a lecture and they don’t have enough space, they just give the lecture outside and are very happy about being so popular. It’s a kind of tradition that just keeps running and I think it’s very much a political choice, about what kind of society we want to live in. In the US, for example, education is connected to the class system. So if you don’t have a degree, it’s very difficult to find a good job, so basically only kids from rich families can afford to go to university and that’s how you structure society. It was just recently published some comments from somebody who was saying: “If we will cancel student debts and make education free, then who will sign up for the army?” Because it’s a strategic way to control people who finish university with a big debt, so they have to get any kind of job to pay their debt: it’s a feudal system. So that’s my explanation of the reasoning behind that. It’s not because it’s expensive, it’s just built to be expensive for social reasons. I would be interested to hear your critique of the Western way of organizing contemporary art systems and you can see this now not only regarding education but also thinking about art institutions: if you’re in the process of building and shaping your own way, how would you do it differently? Would you try to do the same?

Jai

We have different contexts between Asia and the Western. That’s why we have different problems and different methods regarding the art institutions, for example, but also for the people, and for the artworks. It’s just talking about the different contexts and different areas where we live. That’s why there is a difference between Indonesia and Western, and it’s not just talking about what is good or bad: we have our own perspective, which is different because we live in different contexts.

N&P

But what specifically wouldn’t you implement that you see in the West, is there anything that you will try to avoid?

Jai

I’m not sure because, like I said, there is a different context with our place in Indonesia. We can try, for example, with the education program, that is quite a new thing for me. For example, in Indonesia the teacher is very powerful, you must be attending a structural study, you don’t have the freedom to choose which studies you’ll do, but I see that in Europe there is more freedom for the student to choose what to do: you don’t have just to attend a class, you can do your course on your own and after you can present something that you are researching on, and that it’s new for me.

Jatiwangi art Factory is a community, founded in 2005, that conceives contemporary art practices and cultural practices as part of the local life discourse in a rural area. They have been carrying on many different initiatives, always involving the local public, such as a video festival, a music festival, a residency program, a discussion series, and a TV and radio station. Jatiwangi district has a long tradition as a roof-tile producing region in Southeast Asia, and JaF considers clay as the tool through which encourage local communities to create a collective awareness and identity for their region, in order to promote a better life for future generations and a collective happiness for the community.

Terrakotta and clay are deeply connected to the soil, so in this sense, “terra” is not only conceived as a material, but also as a land, a territory, an idea. Through collective everyday practices, agreements and negotiations with institutions and politicians, they aim to change for better the cultural landscape of their city, in a way that pays respect to the traditions and the dignity of the local communities. They work in a perspective that connects the local dimension with a global international network, through which they manage to establish different collaborations, promoting an optimistic and active way of looking at the world.

Previously, the work of JaF has been shown at various venues in Indonesia and abroad, including Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul (2020), the Asian Art Biennial, Taichung (2017), the Gwangju Biennale (2016), Copenhagen Alternative Art Fair (2016), SONSBEEK ’16, Arnhem (2016), Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (2013), and the Jakarta Contemporary Ceramic Biennale (2012).