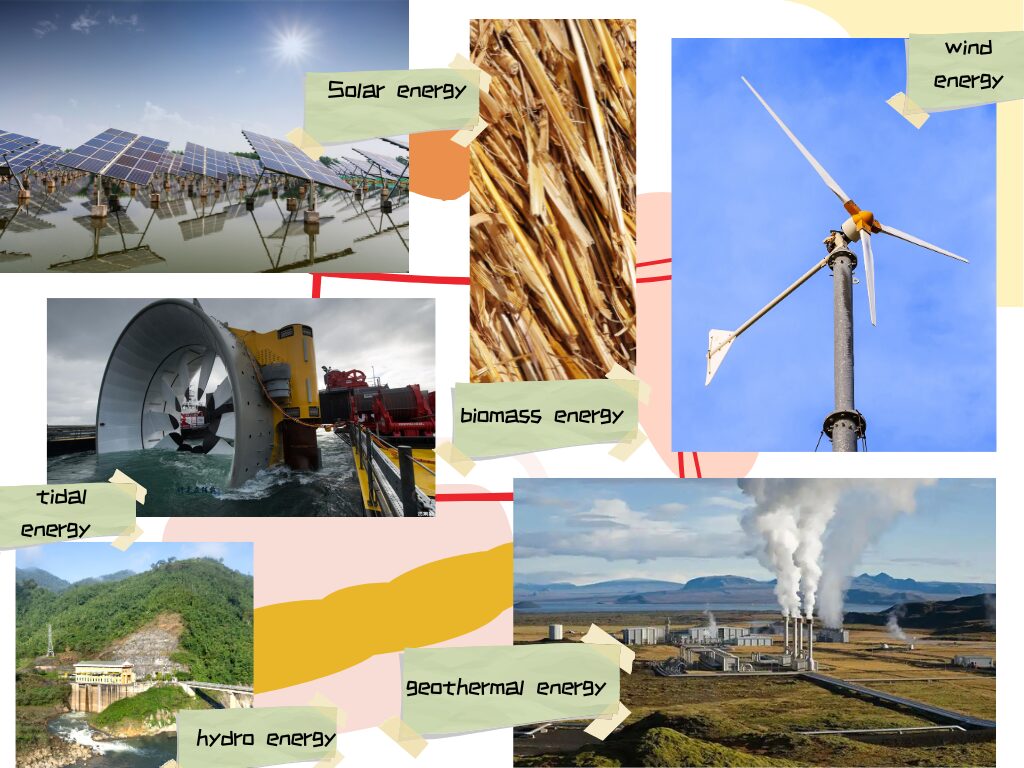

When it comes to clean energy, what comes to mind?

Solar power, wind power, hydropower?

Biomass, geothermal, tidal energy?

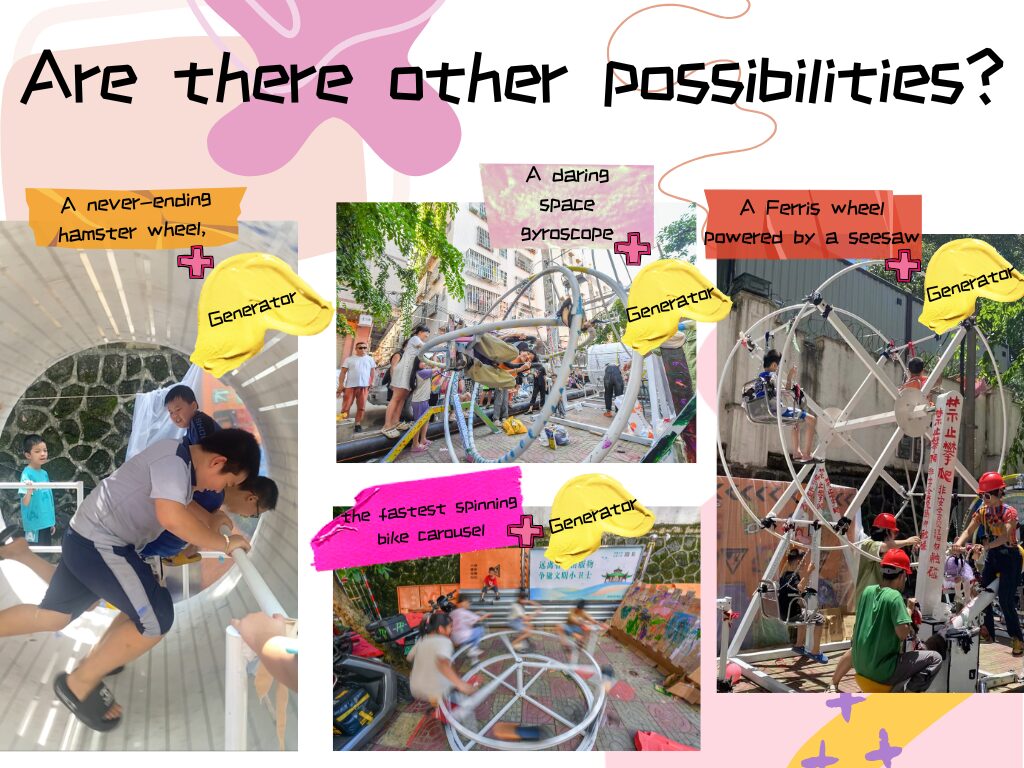

Or are there other possibilities?

The examples mentioned above all come from the “No-Wall Playgrounds”-“Playground without Walls.”

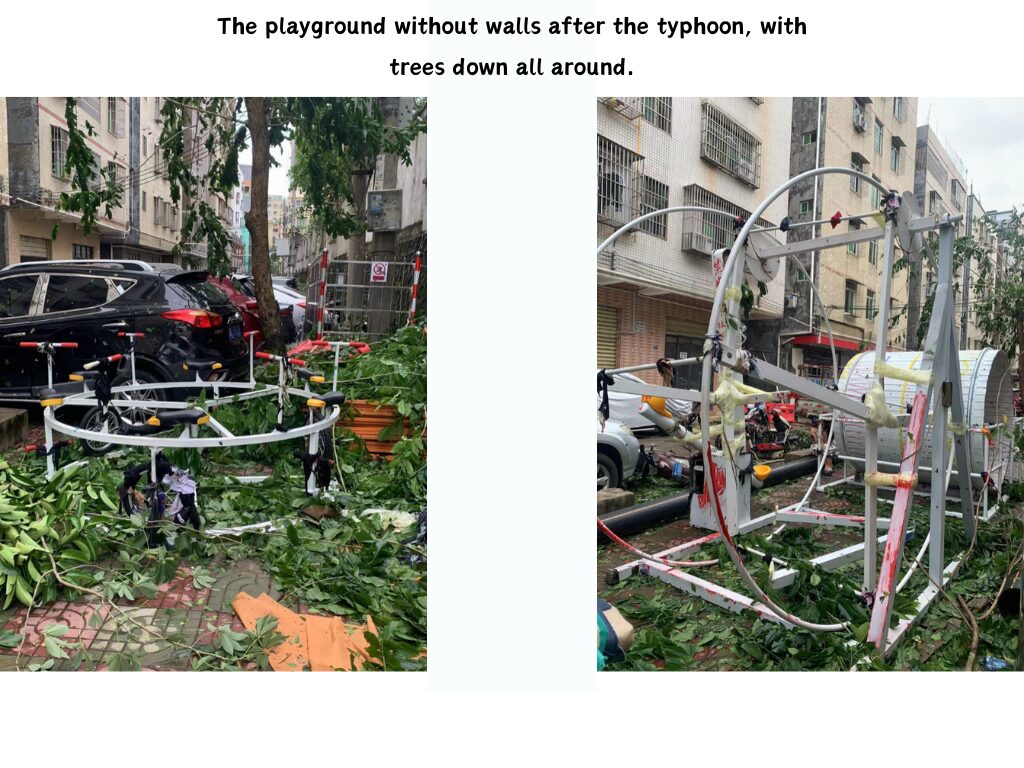

This August, 2024, we built our first No-Wall Playground-“Playground without Walls” in Haikou’s Binlian New Village, Hainan Island, China.

Together with local kids from the urban village, we designed and constructed these structures, which can be quickly assembled and disassembled—like an oversized set of LEGO blocks.

They withstood Super Typhoon “Yagi,” which hit with winds over 17 levels, without a scratch.

This article offers a complete story of the birth of the No-Wall Playgrounds-“Playground without Walls”, showing what we accomplished this August, introducing our team members, and outlining the long-term plans for the playground.(To be continued)

After the typhoon, we’ve been staying in touch with our partners in Hainan through our community, observing how the storm has affected their daily lives.

In these conversations, two main challenges emerged:

- Windows damaged by the typhoon.

- Power and water outages in the aftermath.

Inspired by friends like Jimu in the playground community, we started wondering: could we use the joy of the playground and its engineering principles to respond to these pressing issues?

One of the core principles of the No-Wall Playgrounds-“Playground without Walls” is to always respond to the immediate, real-life situation. And so, this brainstorming session began.

During our playground project, we encountered pollution and waste issues prevalent in the traditional playground industry—such as engineering plastics pollution and the overuse of non-renewable energy.

In designing our playground equipment, we opted for renewable materials and clean energy sources.

Throughout the exhibition period, these play structures were constantly in motion, with kids joyfully pouring their energy into them. This got us thinking: could we convert all that joy into usable energy?

As a combination of participatory art and engineering,

how can we engage with climate-friendly issues?

As a project that combines participatory art and engineering, how can we respond to specific local issues? This question reminded us of an example—South Africa’s Playpumps.

A failed attempt? A public embarrassment under the spotlight?

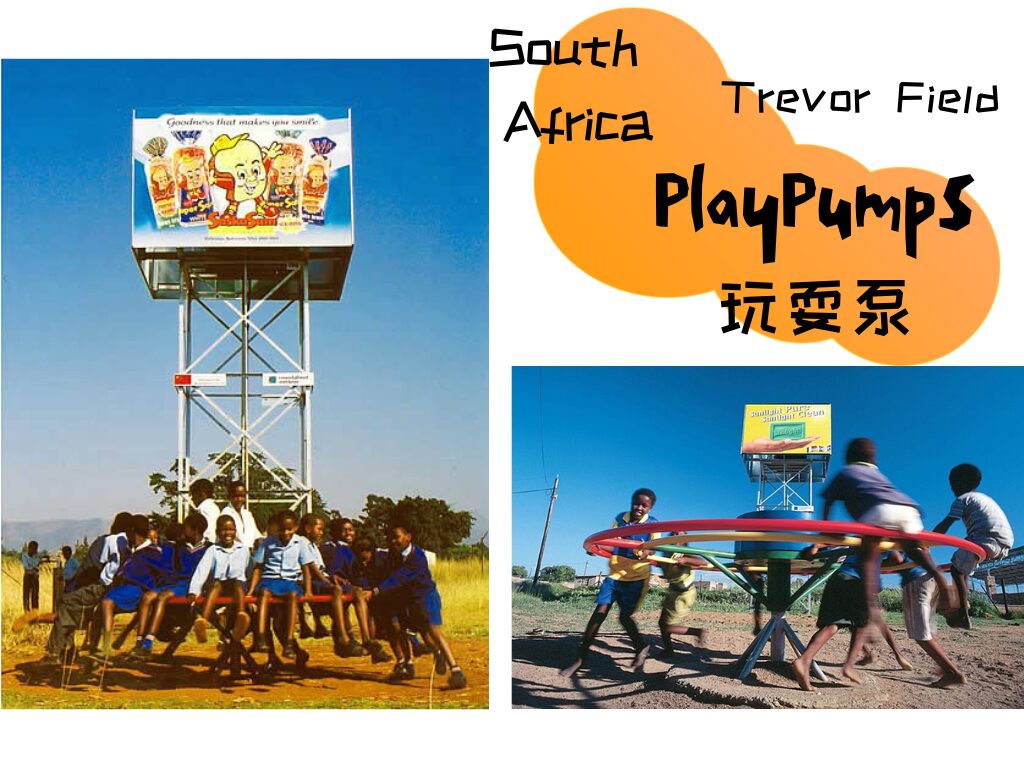

In many African regions, accessing water is a significant challenge. In numerous local villages, women often need to walk around an hour to the nearest water pump. The pump is hand-operated, requiring physical effort to supply enough water for the entire family’s daily needs.

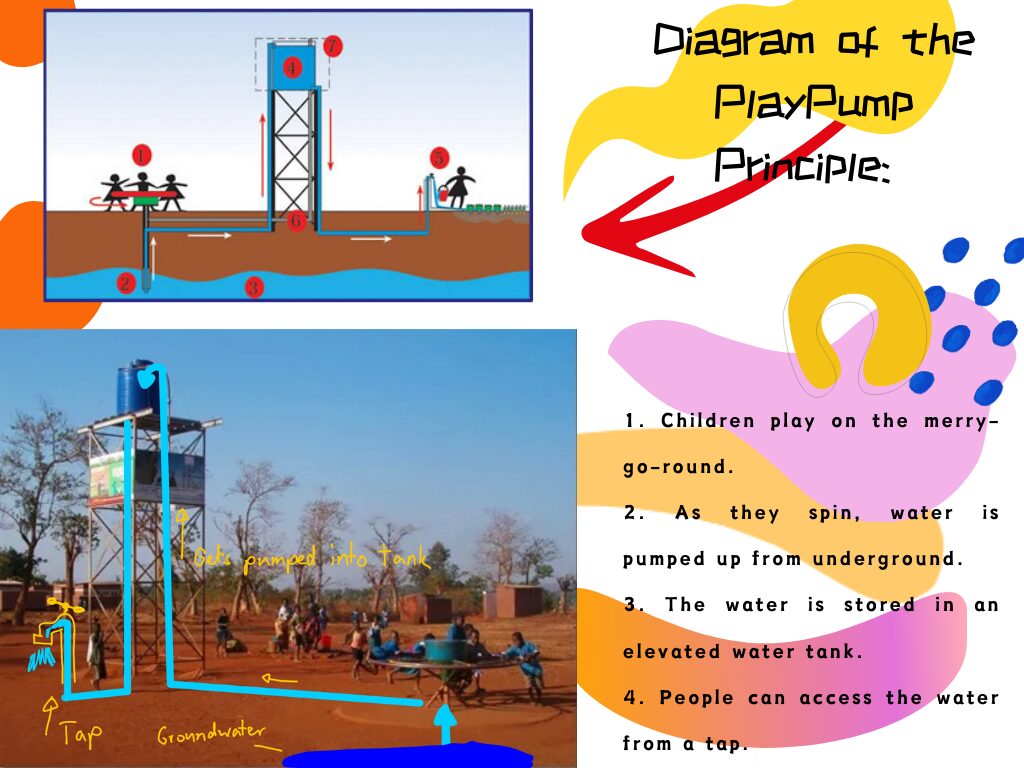

Retired product manager Trevor Field noticed a device at an agricultural fair, invented by drilling engineer Ronnie Stuiver. This device is a rotating structure that attaches to a water pump, enabling it to draw underground water into a 2,500-liter tank placed seven meters above ground when rotated. The tank is connected to a faucet, where people can collect water.

According to the manufacturer, this pump can draw 1,400 liters of water per hour from a depth of 40 meters, with any excess water redirected back underground.

Trevor Field envisioned that the elevated water tank could serve as an advertising space, and the revenue generated from the advertisements would sustainably support the long-term operation of PlayPumps. Trevor, an excellent product manager with a clear vision, led the project to find its first investor five years later, resulting in the construction of the first PlayPump in South Africa.

Five years after that, PlayPumps gained significant international attention. From the World Bank’s Development Marketplace Award to the Gates Foundation, the One Foundation, USAID, and even then-First Lady Laura Bush, PlayPumps attracted substantial funding, with charitable donations totaling over $60 million.

PlayPumps became the ideal model for countless charity projects. However, as the pumps were widely used across Africa, the problems within the project slowly became apparent.

Many began referring to PlayPumps as “the shame under the spotlight” and “a complete failure.”

1.People discovered that the “PlayPump” was inefficient. The UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) recommends that each person needs 15 liters of water per day. To meet the target of providing daily water for 2,500 people per pump, children had to play for 27 hours a day.

2. The installation cost of a PlayPump was very high, around four times that of a regular hand pump. In some cases, during the installation of PlayPumps, the original hand pumps were removed, making the PlayPump the only water source for the village. When the PlayPump broke down, it often went unrepaired for long periods due to a lack of timely maintenance and replacement.

3. The PlayPump’s method of play and enjoyment was very limited and could not engage children for extended periods. When children were unwilling to play, local women had to exert significant effort to collect water, as the PlayPump was more physically demanding than the hand pumps.

Is PlayPumps really a complete failure, a disgrace under the spotlight?

Let’s not answer this question just yet.

We’d like to introduce the attempt made by “Playground without Walls”

This August, we worked with local children and adults to co-design and build a playground in a community village in Haikou.

Initially, the playground was created to respond to the local “The Kindergarten without Walls.” Hao Duo, an artist, opened a small shop called Banban Grocery in Binlian New Village, where he learned about the unique situation of the children in the area. Over time, the grocery shop became a space where children in the community could initiate activities, and adults provided companionship and support.

We discovered that the kids have very limited space to play in their daily lives. The facilities in the community are mostly designed for adults and seniors, leaving little for the kids. Parents also lack the time to take their children to other places to play, so the kids are often left to roam the community on their own.

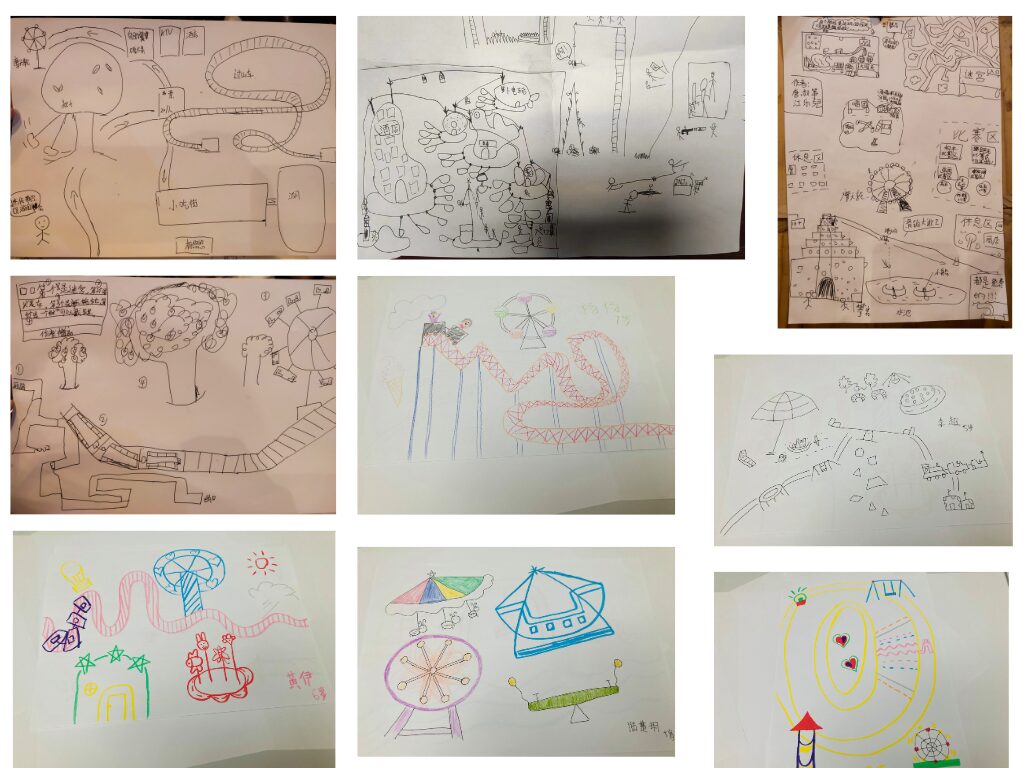

During the preparations for the third Playground without Walls Children’s Art Festival, we decided to create a playground together with the kids.

The playground the kids imagined often featured roller coasters and Ferris wheels. In response to the conditions of the urban village, we designed the playground equipment to be powered mainly by gravity and wind. All the facilities are designed to be easily disassembled and reassembled, like a giant set of Lego blocks.

In the design, we incorporated sensory experiences that are crucial for growth, such as visual, auditory, tactile, proprioceptive, and vestibular senses—experiences that are difficult to fully provide through a phone screen.

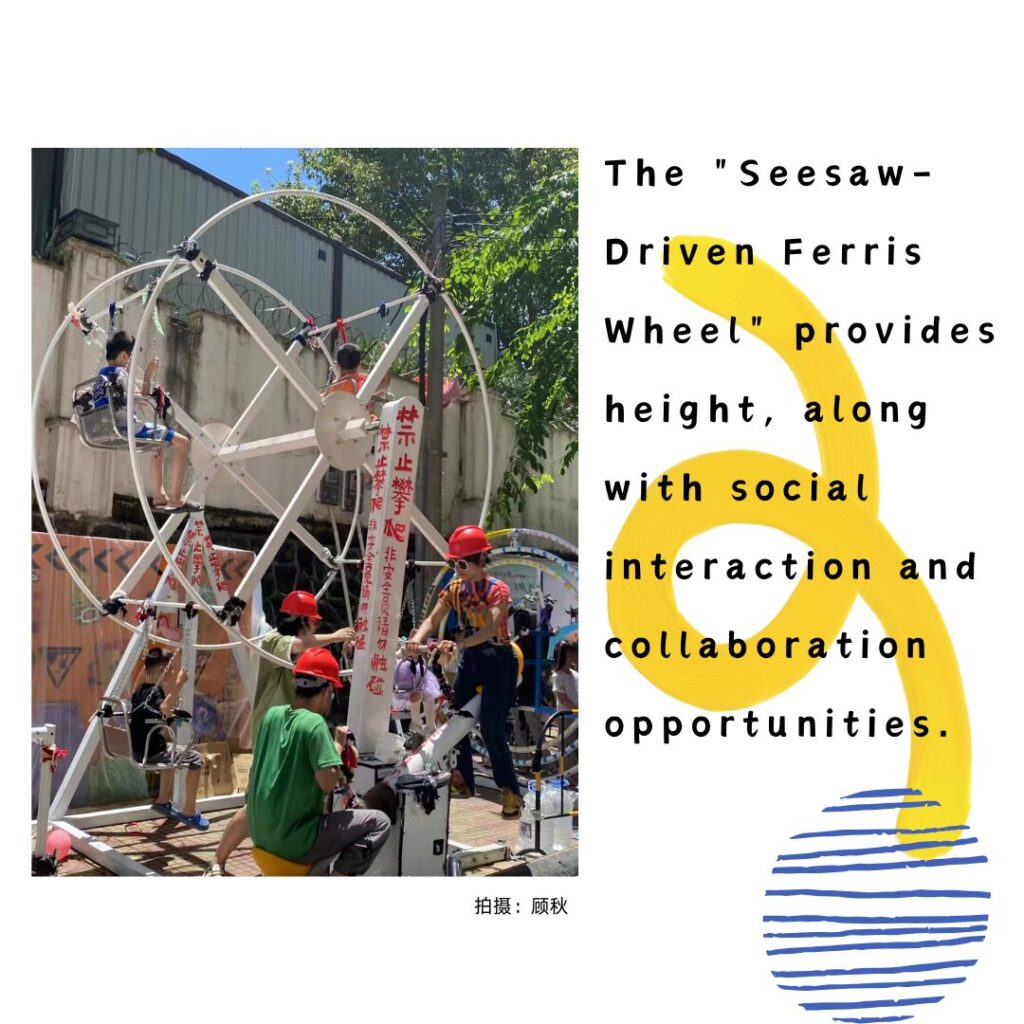

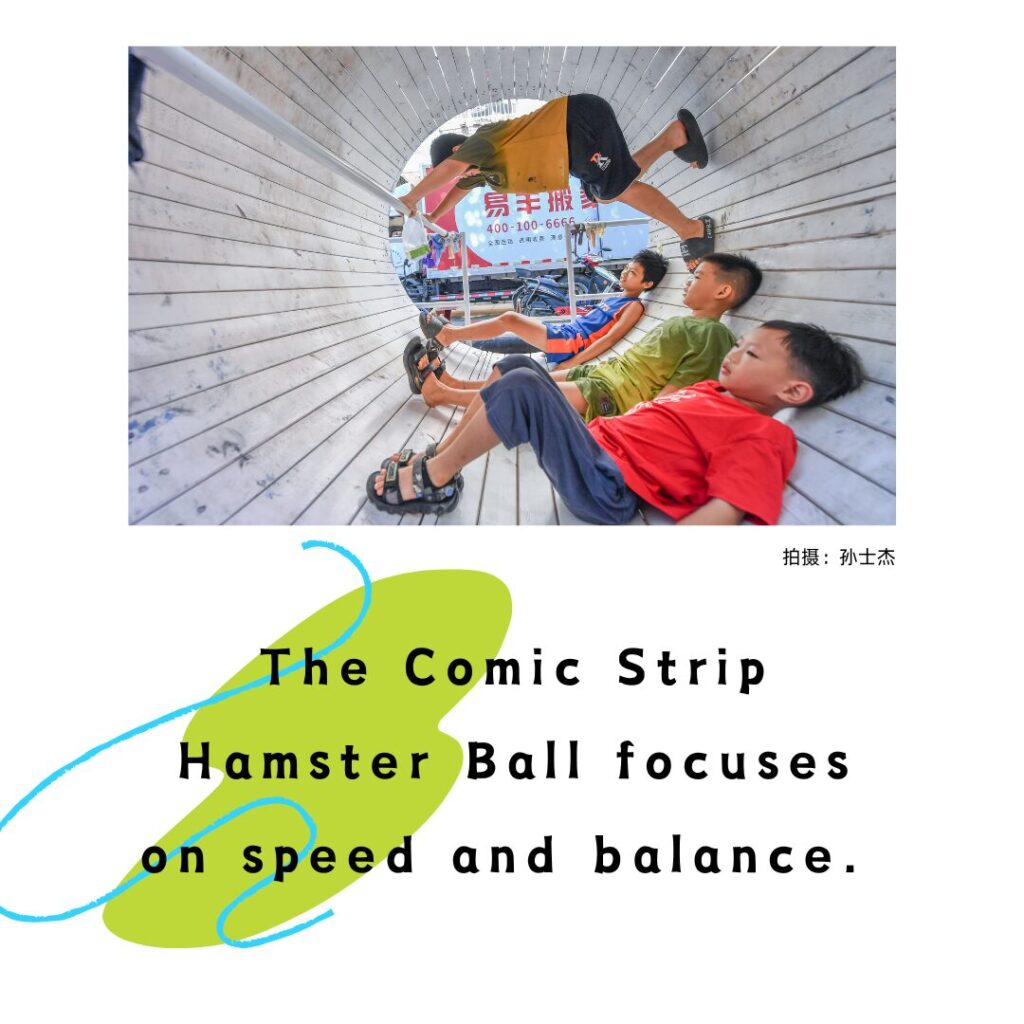

For the playground equipment, we analyzed why people enjoy roller coasters. Roller coasters provide four main sensations: weightlessness and overload, height experience, dizziness, and speed. We broke these sensations down and incorporated them into four different pieces of equipment.

We placed the sensation of weightlessness and overload into the Space Ring, the height experience into the Teeter-Totter-Powered Ferris Wheel, dizziness into the Bicycle Roundabout, and speed into the Hamster Ball.

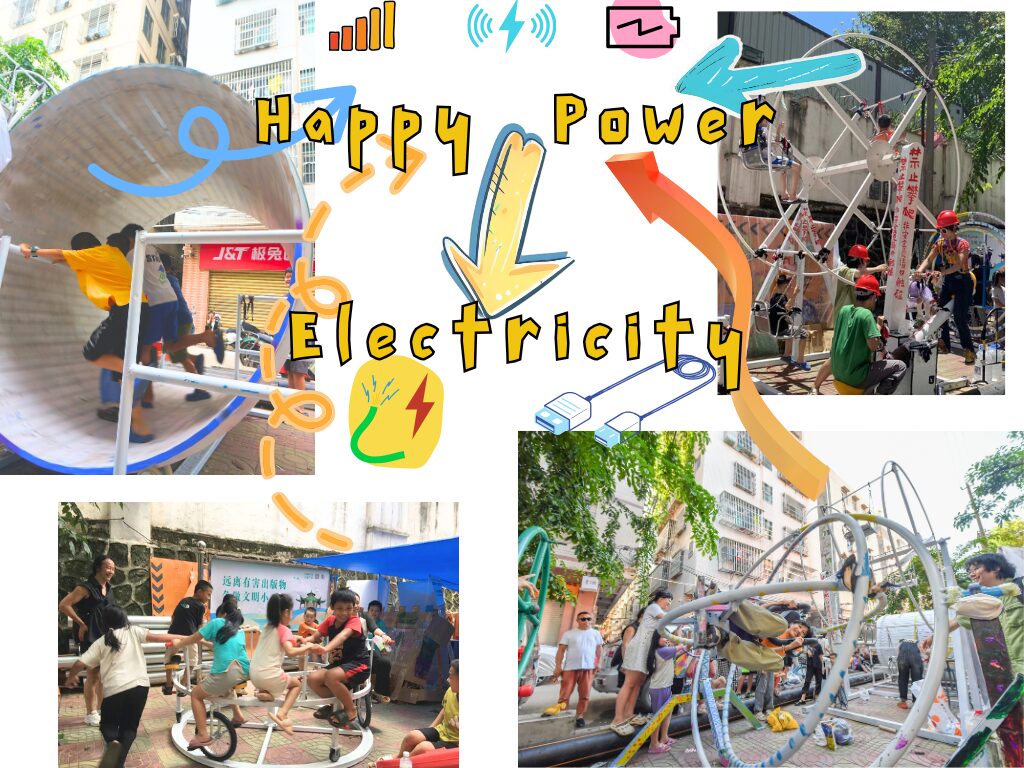

From the moment the playground equipment was installed until we locked them up before the typhoon hit, they never stopped. From morning to night, children were sweating it out on them. Seeing this, Yam, Kathleen, and Lin Kexin (a child) suggested: “Why not add a generator?”

This was a great suggestion.

After the arts festival ended, Super Typhoon “Yagi” (level 17 or higher) made landfall in Hainan. For some time after the typhoon, the local neighborhoods faced issues like power and water outages.

If energy could be generated from the fitness and playground equipment in these neighborhoods, people could charge their phones, power banks, emergency lights, and more, right on the spot, with the entire charging process happening through joyful physical interactions.

The play also provides a way to release the emotions built up during the aftermath of the typhoon, playing an irreplaceable role in the emotional and mental recovery of the community.

Playground without Walls Activities in Dali: “The Power of Play”

Before the typhoon arrived, we received information from multiple sources suggesting that the playground needed reinforcement. From an engineering perspective, these reinforcement proposals were excessive. If we followed them, they would not be efficient, might not actually help, and could result in waste.

For example, tightening the space ring more wasn’t necessary. It has a small wind-facing area, and its base is very heavy, so it couldn’t be moved by a typhoon stronger than level 17. If we used other methods to reinforce it, it could increase the wind-facing area and actually risk being blown over.

We also wanted the playground to address the current climate-friendly issues, in a joyful way.

So, under Melon’s leadership, we chose simple, locally available materials, like wide tape, hemp ropes, and some wire, to reinforce the playground. The Ferris wheel was taken down and tied to the central axis of the seesaw.

A friend we met at the Climate Impact Conference described our approach as creating a resilient playground for the city with the least carbon footprint possible.

After the typhoon passed, Dun Dun, our team member, was the first to arrive at the site and carefully checked the playground, finding everything intact and unharmed.

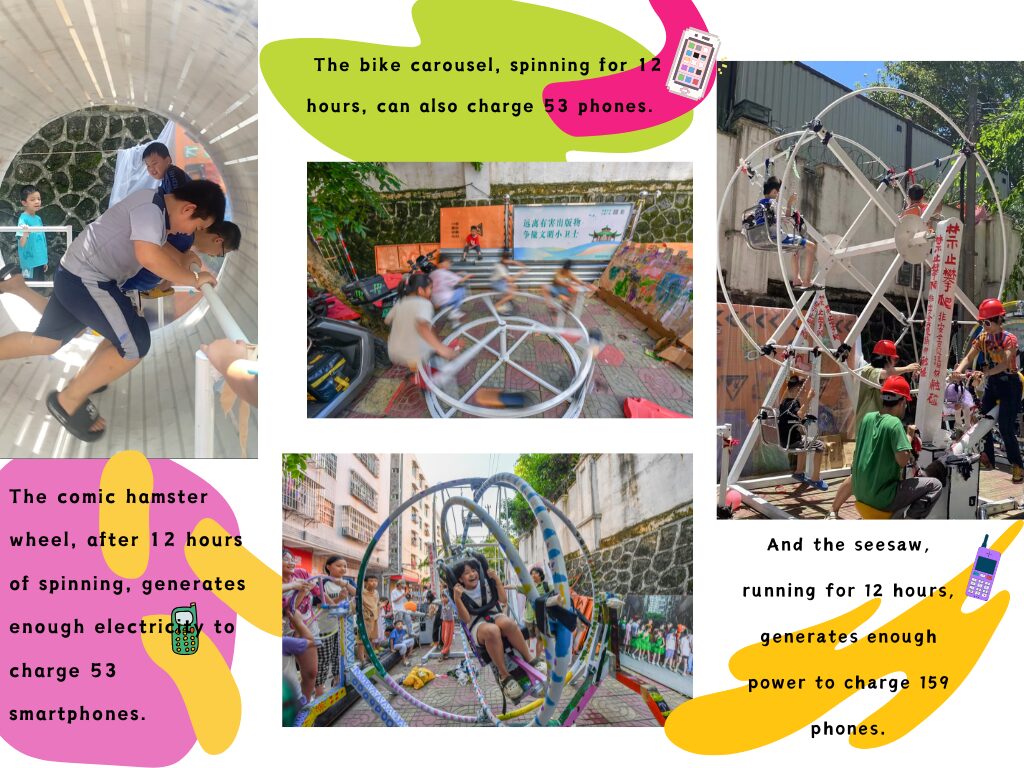

In response to the community’s power and water outages, we conducted two rounds of testing on the energy generation design of the playground equipment. The test results were as follows:

- The comic book hamster ball, after running for 12 hours, can fully charge 53 mobile phones with a battery capacity of 5000mAh.

- The seesaw, after running for 12 hours, can fully charge 159 mobile phones with a battery capacity of 5000mAh.

- The bicycle carousel, after running for 12 hours, can fully charge 53 mobile phones with a battery capacity of 5000mAh.

At the International Climate Impact Conference, we received a lot of feedback from friends who strongly resonated with the power of Playground Without Walls: Powered by happy. Powered by fun.

We also hope that “happiness,” as a form of energy, can bring magical “charge” to more people—beyond just the physical energy, but also to those things that are closely connected with the growth of our inner world.

Play is a method for achieving joy, ease, and the operation of metaphors. Moving the body is crucial for the development of the mind. From a psychoanalytic clinical perspective, somatization symptoms are increasing. The difficulties the mind faces lack the space for collaboration and development, being entirely controlled by contradictory compulsive impulses. The mind cannot free itself from the unconscious situations it creates and return to the reality the body is currently experiencing.

From a neuroscience perspective, if the people around us have better brain development, the more instinctive, unconscious collaboration will make our own brains work more easily. It can be said that using collective collaboration to develop a group of brains is more efficient than developing a single brain on its own.

For children, especially, play is a more effective way to face challenges, integrate body and mind, improve the brain’s synchronizing cooperation ability, and return to the present moment.

Scott Osterweil, the Creative Director at the MIT Education Center, was the first to propose the “Four Freedoms of Play.” These are freedoms we may not necessarily experience outside of play:

- Freedom to Experiment: The opportunity to try things out, with creativity and exploration, and to attempt things that might seem a little crazy. Some of these experiments are things that might send shivers down adults’ spines—like physical challenges on the playground—while others are on a smaller scale, like trying a new game with a ball on the playground.

For example: PlaygroundNYC

Children take risks as they adventure through “dangerous” “trash” in the playground.

2. Freedom to Fail: This is a natural consequence of the first freedom, as true creativity and experimentation may not always lead to the expected outcome. This is crucial because children perform very differently when they feel they are being observed or judged compared to when they feel free from observation and judgment. Believing that failure won’t lead to permanent negative consequences allows children to think outside the boundaries they encounter in their everyday lives.

Eg:PlaygroundNYC

3. Freedom to Take on Different Identities: When playing games, children have the freedom to become someone else. While this can involve role-playing (e.g., “I’m the little sister, and you’re the big sister” or “I’m the knight, and you’re the monster king”), it can also be more metaphorical. For instance, a typically shy child may take on a leadership role during play. This freedom allows children to experiment with different personas, helping them explore and develop various aspects of their identity.

The children are playing role-playing games.

4. Freedom to Put in Different Levels of Effort: In play, children are not judged on whether they are “trying their best” in a game. Unlike in the “real world” where performance is often measured, there is no penalty for the level of effort put in today versus tomorrow. This freedom allows children to engage in play at their own pace, without fear of judgment or failure, fostering creativity and reducing the pressure to always perform at their highest level.

The children are playing a balancing game.

Some are putting in a lot of effort, while others are just casually playing.

In play, we reconnect with our bodies, returning to the present moment, exploring the world, embracing life, and experiencing the everyday.

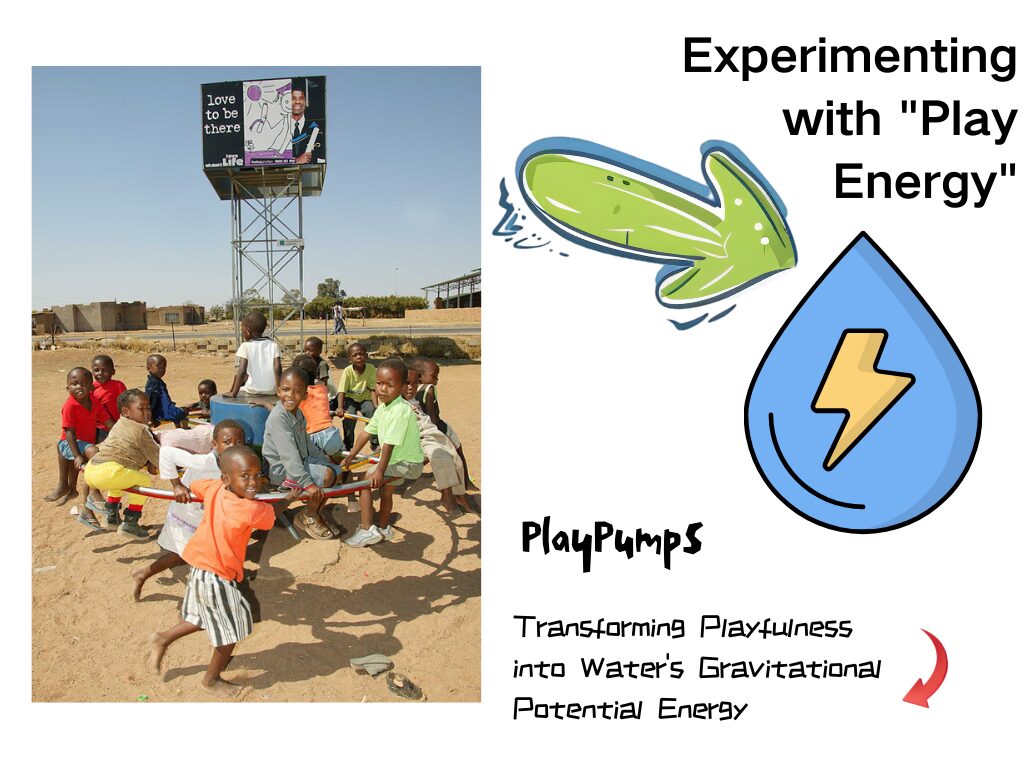

The energy that emerges from play, as a subtle and pervasive force, is what we call “Play Energy”-“Happy Power.”

The power of play exists beyond the dimensions of knowledge and language, operating on a broader, more hidden level.

“Play Energy”-“Happy Power” not only includes this mental strength, but also has the ability to generate electricity or purify air, directly impacting the world in specific, tangible ways.

Hi, Play Energy-Happy Power, this is everyone.

Hi, everyone, this is Play Energy-Happy Power.

We call the energy that people exert during play and recreation, which can be collected and utilized, “Play Energy”-“Happy Power.”

With simple modifications to existing playground equipment, we can easily capture and use this “Play Energy”-“Happy Power” without the need for overly complex designs.

In addition to adding power generation devices to the bicycle carousel, hamster ball, and seesaw, we can also add similar energy recovery systems to equipment like zip lines, swings, and rafting features. Even more large-scale and complex play structures can undergo similar modifications.

For example, we could set up clever wind turbines next to large roller coaster tracks, using the air movement generated by the high-speed movement of the coaster to generate power. In short, any playground equipment with relative motion can be designed or modified to serve as a “Play Energy”-“Happy Power” collection device!

In addition to modifying and redesigning existing types of playground equipment, we can also design and create entirely new play structures based on the principles of “Play Energy”-“Happy Power.” These new devices would not only offer people exciting new play experiences but also collect play energy more efficiently.

When we revisit PlayPumps, can we truly say that we can’t use joyful, artistic, and creative methods to address specific problems?

Is the biggest issue with PlayPumps really project operations and management?

We still believe that the PlayPumps concept was a very good attempt—it opened up a creative dimension for addressing current problems.

In fact, it only needed a small improvement in engineering design. The biggest problem with PlayPumps was that it wasn’t “useful” enough. Also, it could have been designed to be more fun.

Engineering calculations involve not only the mechanical design of the facilities but also cost design, production organization, sustainable maintenance planning, and more. Engineering projects require the involvement of engineers’ thinking in every part of the process.

“Play Energy”-“Happy Power” (游乐能) was first proposed by Melon Ding (小瓜) in August 2024, inspired by the “Playground without Walls” project. The concept and idea of “Play Energy”-“Happy Power” were first introduced by the Playground without Walls team at the 2024 “Impact International Climate Innovation Conference.”

The “Playground without Walls” project was launched by Becca Liu(贝卡) and Melon Ding (小瓜) in February 2024. It was conceived during the preparations for the third Children’s Art Festival of “The Kindergarten Without Walls” and initially aimed to address the needs of the “The Kindergarten Without Walls” in Haikou. Over time, the project grew into an independent long-term initiative.

Rebuild the pillow fort in the living room, and together, let’s reshape the world.